Chicago-based Doblin, Inc. is an internationally recognized innovation strategy firm. Doblin’s staff is composed primarily of business strategists, cultural anthropologists, contextual researchers, design planners and information designers. Doblin is well known for its proprietary innovation landscape diagnostic tool, which is used to identify patterns of innovation within an industry. This article explores Doblin’s approach to treating innovation as a repeatable business discipline. Discussions of BPM or IT are completely ignored in the article, and for good reason—it’s written from a purely business leader perspective. What’s interesting about the article is that you, the reader, will no doubt want to map your knowledge of the “BPM lifecycle” to the “innovation lifecycle” discussed in the article.

Innovation is about doing things differently and doing different things. It fails if costs exceed returns over time. It succeeds if returns exceed costs in amounts sufficient to reward shareholders.

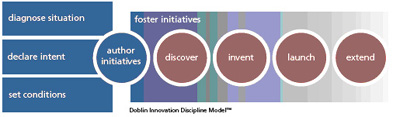

Innovation failure comes from both errors of commission and omission. Doblin’s Innovation Discipline Model provides a framework for categorizing innovation practices. It helps people see dimensions of an innovation competence that may have been previously overlooked. It can increase the chances for innovation success and reduce the risks of innovation failure.

Diagnose situation. Getting the right inputs are important for innovation preparedness.

Look at your enterprise to determine the appetite for innovation, and, if necessary, foster this appetite. Use this model to help take a comprehensive view.

Look at your industry to understand where others are focusing their efforts. Industry players frequently think alike, leading to parallel agendas. This leads to simultaneous invention and continued parity, which in turn reduces the return on innovation as no one achieves sufficient differentiation to increase margins or market share for very long. Knowing where an industry is headed sometimes suggests where not to go. This is a different kind of benchmarking: Here you study competitors to avoid copying them.

Look beyond your industry not only for threats but also for opportunities to borrow ideas emerging in other industries and adaptable to yours.

Look at your customers to find the “latent and blatant” needs and desires that are currently not being met.

Look beyond current customers to find new classes of customers you may attract with the right innovation efforts.

Declare intent. Leaders need to set directions and issue challenges so that innovation efforts align with company objectives. An Innovation Intent describes goals both for thinking differently and for doing different things to achieve something new and important. An Innovation Intent should aim to take the company to a new level or place. Depending on the situation and leadership style, an Innovation Intent can be set more or less collaboratively with your management team.

Set conditions. For effective innovation, some capabilities may need to be augmented, some incentives adjusted, and some processes modified. Priorities must be shifted enough so that taking care of what is immediately urgent does not preclude developing what will eventually become important. The need for some condition changes often becomes obvious once an internal innovation diagnosis is completed and an Innovation Intent is defined. Additional reasons to change internal conditions can reveal themselves as innovation initiatives proceed and hit speed bumps caused by suboptimal arrangements in the enterprise.

Author initiatives. The innovation rubber hits the road through initiatives designed first to develop and then to implement innovation concepts. In our experience, the high level planning for initiatives is best done in group settings, typically for senior business leaders. Groups are obviously more effective when they are well informed, and participants should have had the opportunity to learn innovation principles, to review the diagnosis of their innovation situation, and to absorb or co-develop an Innovation Intent. A workshop setting with a disciplined process can be used to identify opportunity areas for initiatives. Those initiatives that resonate most closely with the Innovation Intent typically get the higher priorities. After the workshop, teams can be assembled for individual initiatives and plans for discovery and invention phases of the initiative are developed.

Foster initiatives. Initiatives, if successful, proceed from a loose to a tight idea and from weak to robust implementation. Along the way there can be fragile stages through which initiatives should be nurtured. At the same time, companies must also end initiatives that are clearly floundering or that do not sufficiently align with growth objectives. This decision process is an inexact science, full of human beings. It is not advisable to do clinically. Typical stage-gate processes are blunt instruments, often run more for the convenience of leaders than for the nuanced support of individual initiatives. Some gates can present too high a hurdle, killing initiatives that deserve nurturing, and some too low, extending the life and costs of an initiative that has diminishing chances for impact. Getting all this right requires tinkering and more senior executive time and timing flexibility than is typically devoted to initiative oversight.

Innovation initiatives. Project teams undertake the steps depicted by the red circles of the model. Staffing will change as an initiative moves from concept development to implementation of an innovation idea. Throughout the process it is important to have a strong functioning relationship between an initiative project leader and an enterprise representative to the initiative. It is also important to staff a core and extended team appropriately, and to clear schedules of participants so they can devote sufficient time to the initiative.

Discover. In the first stage of an initiative the team develops a detailed understanding of the opportunity area. Discovery is initially customer-facing and aimed at identifying needs. Latent needs are ones that no one has previously discovered. Blatant ones should be obvious but can hide in plain sight because of industry assumptions that that they are intractable. Typically, existing research undertaken in the service of extending business-as-usual is of little use in informing innovation development. It’s more likely that various forms of qualitative research (especially ethnographic) are most effective.

As needs are uncovered and business concepts emerge to address them, the discovery effort shifts to an industry and internal focus. Teams look for internal capabilities as well as barriers, and for previous analogous experience within the company and industry. The focus also shifts to quantitative efforts to size the business opportunity. The more disruptive the concept, however, the more difficult and perhaps self-defeating it is to concentrate on sizing. Assumptions nest within assumptions that nest within assumptions, any of which can radically throw the estimate off.

Invent. Invention involves a leap of synthesis from insights about needs and desires to a set of actions that deliver value, serve customers better, and reward shareholders. There is no way to invent through analysis, though research analysis should inform synthesis. Invention is greatly facilitated by relevant content experts and by experts in describing and depicting emerging concepts. They work together to create ever tighter business concept stories and illustrations. Team members learn from these and share them with key audiences for feedback.

The discovery and invention phases dovetail. Initiatives are discovery heavy at the beginning and invention-heavy near the end. The two phases typically end at the same checkpoint, when an initiative is formally reviewed and evaluated for implementation. Initiatives are sometimes redesigned or terminated, perhaps the result of a dysfunctional team or an anticipated opportunity that has turned out to be illusory or misaligned. Project and enterprise leaders should have an ongoing dialogue about these issues, and provide feedback to and seek input from initiative sponsors.

Launch. A market-facing implementation team is established and project management may change hands to emphasize accomplishments within and around the organization. The concept development team may make strong recommendations concerning new enterprise capabilities necessary to implement the concept. It may also be productively involved in occasional progress reviews. The implementation team will focus on identifying the first-generation set of features to make the concept compelling to customers, the ways to get the necessary work done through or outside the normal channels, and identifying the quickest and least expensive way to pilot the concept, get feedback, and then launch.

Extend. With a successful launch, efforts turn toward growing the concept quickly enough to keep ahead of copycats. Optimally, the underlying concept provided room for third parties to gain benefits by jumping on the business platform. This allows the business to grow much more quickly than internal development alone would allow. Whether or not a platform is achievable, a growth path must explore new geographies, segments, and extended offerings. Past successes suggest that good innovations typically become profitable quickly and have a path to expanding profitability. At this point the initiative is absorbed into the company and becomes managed as an ongoing business.

Having described a fundamental innovation discipline model here, in a future article we’ll take a look at the ten types of innovation, and suggest how the disciplines of business process management can map onto that model. Measurable, repeatable processes are at the very heart of any innovative business.

Innovation is about doing things differently and doing different things. It fails if costs exceed returns over time. It succeeds if returns exceed costs in amounts sufficient to reward shareholders.

Innovation failure comes from both errors of commission and omission. Doblin’s Innovation Discipline Model provides a framework for categorizing innovation practices. It helps people see dimensions of an innovation competence that may have been previously overlooked. It can increase the chances for innovation success and reduce the risks of innovation failure.