Look at any book on business process management or improvement these days and you’ll see a good amount of advice being expended on the creating, chartering, nurturing and managing of process design, or improvement, teams. Typically, these are made up of employees who perform the processes being improved along with a gaggle of supporters, technical experts, and the like. In organizations where process management is a goal, a similar phenomenon takes place, typically with teams of mid-level managers nominated as “process owners” accompanied by a host of process excellence specialists and various other coaches or hangers-on. Look inside a corporation that has gotten into process work with technology as the driver and you are likely again to find a huge complex infrastructure of improvement teams, steering committees, regional oversight committees of site coordinating teams, centers of excellence, and on and on. The complexities of these team infrastructures tend to mirror the organization’s structure, with tiers of interlocking teams for every level that exists in the company.

Is this a good thing? Usually, not very. The teams frequently tend to either ignore each other or bicker over tools and methods and get territorial, and then they burn out after documenting the processes like maniacs for a time but never quite getting to any real improvement or management.

So where on earth did the idea come from that creating a bureaucracy was the way to do BPM? Sad to say, from us. That is to say, it came from the various consultants and advocates who over the past 15 years have advised companies on the worth and mechanics of process improvement and management. My colleagues at the Performance Design Lab (PDL) and my former colleagues at the Rummler-Brache Group all recommended these steering team/design team infrastructures, and so did all of our competitors. So now it’s a given. But once upon a time, there once were no such givens.

The process improvement methodology invented by Geary Rummler and friends in the early 1980’s and first deployed at Motorola was quite different from today’s approaches. It started experimentally, on a small scale, and then eventually got applied to whole business units as the methodology matured. But in those early outings, there were no steering committees or design teams. The people we worked with were the executives. It was the leaders of the business who were the process improvers, the process owners, the process team.

A project went like this…

We (Geary and I) would get an appointment with the head of a given business unit. We would ask that person to talk about the state of the business and the challenges facing it. From that discussion we would, together with the client, identify a critical business issue and determine if a process improvement solution would help in resolving the issue. If the answer was “yes”, or perhaps only “maybe”, the leader would convene a meeting of his direct reports. Meanwhile Geary and I would gather background information on the organization, on current performance, and on the target process.

In a series of three or four half-day executive meetings, we would map the current process (high-level, major steps) with the executive team, identify the disconnects, determine why they were happening, decide on what should be happening, and then map the desired process. Today’s methodologies would take weeks or even months to accomplish as much. Our elapsed time was a week or two.

Then something almost miraculous would happen. The executives would order their people to implement the new process – and it would happen! No elaborate presentations, little if any “upselling,” no dawdling, no “transition period” or “management of resistance to change”. When the SVP turned to the VP and said, “Now make it happen,” it would happen.

Now to be honest, we modified this approach after a couple of outings, and the sessions began to be attended by more than the executive team; instead, we augmented that group by inviting in many of the senior managers from the next level, sometimes from the upstream and downstream organizations, and often some technical experts as well. So the team was more of a horizontal strip of the organization sprinkled with a diagonal slice (or something). Then when a technical question came up, we were not as often stymied while somebody ran off to find the technical expert who could answer the question, and when the SVP said, “Now I want this done,” there was a realistic dialogue about what it was going to take, upstream and downstream, to put that new process in place.

But still, it was the executives doing the process analysis, the executives creating the process redesign, the executives committing themselves and their resources to implementation right on the spot. And the results spoke for themselves. The first big project we did this way reduced the cycle time of an order fulfillment process from 17 weeks to 7 weeks in 6 months. The second project reduced a worldwide manufacturing and fulfillment process from 17 weeks to 10 weeks in 6 months to 5 days after 18 months. With those kind of results we were able to convince many other divisions and functional areas of the company that this process stuff could really pay off, and quickly. And as long as we were in the general vicinity, organizationally speaking – that is, in the semiconductor product sector where these first big successes took place – it was accepted practice to have the top management team do the process redesign work.

So what happened? Inside Motorola, the process improvement methodology eventually spread everywhere, and got combined with concurrent efforts in statistical process control to become the Six Sigma program. And the six sigma approach did use a team infrastructure composed of a steering team, an improvement team and a statistics coach. So that kind of bureaucratic construct came from the six sigma methodology, and the executive team role in process improvement kind of faded away.

Meanwhile Geary Rummler also applied the process improvement methodology at other companies, where there was not the same readiness of senior executives to do the process work themselves, and so the team infrastructure model that evolved at Motorola gradually became the de facto standard for how to run a project like this.

There was, however, another reason for this drift away from the direct involvement of executives in process improvement projects: At that early time we didn’t fully recognize that often what could be wrong with a given business process was not actually in the process itself but in the management system that governed the process.

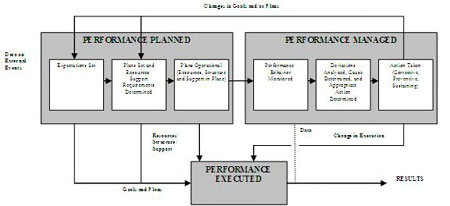

Over many years we have developed a model of an effective management system (shown in Figure 1). In this model, the business (or work) process is called “Performance Executed”, but it is driven by what management decisions and actions take place in “Performance Planned” and it is governed by management decisions and actions in “Performance Managed.” So with this model today we can analyze a business process and identify its disconnects, but then categorize them as deficiencies inside the process itself or as deficiencies in the management system.

With that understanding, we realize in hindsight that one reason the early Motorola work with executives was so effective, and the remedies could be put in place so quickly, was that very often the disconnects were management disconnects, not process disconnects.

Here’s an example from that very first successful project: The executive team was looking at how long it took to produce a custom-built integrated circuit and were chagrined that they were lagging far behind competitors. When they discussed the reasons for the various delays and complications in this process, one of the biggest issues was the tendency of the Division GM to talk to some customer, promise them a quick delivery of product, then go down to Production Control and insert this new order into the middle of everyone’s plans. As the Division GM listened to example after example of the havoc this caused on the production system, he finally admitted that instead of adhering to the FIFO model of production control that his organization advocated, he was applying his own “last customer I talked to” prioritization system. And he promised to stop doing that once his people gave him a means for getting his hot order into the queue with a reasonable due date.

So it was a management disconnect that got addressed that day, and the implementation, while immediate, was far-reaching in its impact. And many of the disconnects addressed by that team were also management disconnects, ones of their own making and addressed by forging agreements to manage the business more collaboratively and with clear, visible standards. The work process (i.e., what the engineers and production people did) changed relatively little.

Alas, the Executive process improvement project has largely gone away. But it has the same potential for powerful results as it ever did. That’s why our attention today is not on work processes by themselves but on the interaction between work and the management system that governs that work.