This article is the first in a series of four to address the role of decisions and rules as an integral part of systems designed to adapt dynamically to changing environments. Here you will be introduced to critical elements of decision processes within Adaptive Systems, techniques to capture and communicate them as well as concepts to apply to make that adaptation more autonomic.

A concrete example will be used to describe the techniques, although their applicability should not be considered limited to that one domain.

Impulse Buying

Most everyone has noticed the various tempting items that are strategically placed at the checkout stand in retail stores. Chocolate bars, magazines and horoscopes, displays abound with a mix of items intended to appeal to that ‘last-minute’ buying decision as shoppers wait for their turn at the till. More recently, this approach has been applied to on-line shopping as well, with a very real difference. In the physical world, displays are static, and only refreshed periodically. Effective on-line experiences are tailored as much as possible to the specific individual shopper. One of the business challenges faced by on-line retailers is how to change the mix of checkout promotional items to reflect what the specific individual shopper is most likely to add to their cart before clicking ‘submit’.

Decision Profiling

The underlying principle of increased individualization of experience is hardly limited to on-line retailing. Faced with a bewildering array of options, consumers everywhere gravitate to selections tailored to their interests. How then to accomplish this?

To begin, the Predictive-Emergent design pattern1 describes how a base set can be presented and then, extrapolating from actual experience, refines that set. The cornerstone calculation for achieving this refinement stems from the Bayesian Inference model. This model supports calculations for arriving at a probability that one hypothesis is more valid than another.

In the case of Impulse buying, the hypothesis could be that someone shopping for sneakers may be more interested in socks than gloves. The base set may be an entire catalog, or promotional subset. The emergent set is based on comparison of items viewed during a session, or even across sessions. A weaker version of this is shown on Amazon where shoppers are presented with the information that others who viewed this same item were also interested in specific other items. This is weaker inasmuch as it is not tailored uniquely to the individual or the specific site visit.

To extend our example, if the shopper had been evaluating footwear for rally racing, they may well be more responsive to a last minute presentation of racing gloves. The context is the most significant determinant of relevance.

Capturing Context

Context is difficult to express in isolation of the attributes it contains. In our example, the shoppers context may be racing accessories for some purposes or shoes for another. The attribute ‘size’ is a useful example. The racing gloves will have one meaning for the size large, socks quite another. Data modelers have long resolved this issue with product_type_size attribution. However, for purposes of decision modeling, we need to express the rules governing the logic, not the data. For this, we can use ValueGroups.

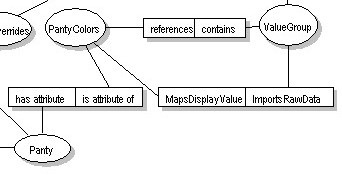

Figure 1: ValueGroup Object-Role Model

Object-Role Models2 can be generated using Visio. Their strengths and weaknesses as a modeling tool is beyond the scope of this article, however, given the accessibility of Visio as a tool for depicting design artifacts and their favorable reception during the engagement that gave rise to this example, they are not without some merit.

In the example above, an on-line retailer needed a means of depicting rules governing product descriptions to be assembled and displayed on their e-Commerce site. The model above shows that a product has colors and those colors are related to a specific value group that manages the importation of data values from an external system and maps those values to display characteristics. Value Groups contain data, meta data, rules and meta rules which taken together can provide a context for a decision.

Managing Multiple Contexts

It can be tempting to think of a context of contexts, but that quickly becomes confusing, especially when presenting combinations of data and rules to users for validation of their requirements. Accordingly, we can benefit from the work done in Aspect Oriented Programming, Analysis and Design. Using their terminology3 Aspects are the sets of concerns that can be segregated and handled as discrete groups of logic and data. One of the most difficult aspects of…aspects…is determining which of a number of valid approaches should be selected for a given context. One of the methods for capturing this in requirements is using ORM notation to capture value groups and then to associate overrides for predictable situations.

Figure 2: Setting a context for product attributes via an override hierarchy

In figure 2 you see a more elaborate object role model that shows the relationship of value groups to both general sets and a specific attribute set (colors). The introduction of both attribute overrides and an override hierarchy allow users to identify cases where particular values of a value group should be either suppressed or promoted.

To bring the discussion back to our on-line retail example, one of the attribute overrides may be price. Having identified that a particular customer, in a specific shopping session has interest in a set of promotional items, these may be presented at check out. However, where the override hierachy has been defined to include such things as frequent shopper status, the override selected may be a discount formula greater than would have been presented on the basis of product alone. All of these decision elements can be captured, expressed and validated through the requirements and design stages using this approach.

Adapt and Thrive

Organizational agility is the lofty goal of myriad IT tools and techniques. In this article, you have been introduced to the concept of designing for both the predictable and the unexpectedly emergent. Linking requirements and as-built software in ways that can be easily understood by business and technical people alike is a critical factor for success. Expressing related data and rules as concerns and aspects, resourcing those aspects with value groups and managing changes in context with overrides are all techniques that enable speedier adaptation. When used together, they can form the basis for a shared understanding across all the participants in a system, while allowing each individual to focus on their own particular sphere of concern.

Upcoming articles on Emergent Strategy, Exception Based Reporting and Implementing Decision Capabilities in Software will explore in greater depth the ideas introduced here.