This article covers an issue within Business Process Management (BPM) redesign which is often not fully discussed. Frequently, development groups are eager to get the team fully engaged as quickly as possible. Looking at “as is” situations (examining, modeling) may receive slight attention as being “bygones” – “Let’s start with a clean slate.” The issue is deciding how quickly to begin computerized development after a project or analysis has been scheduled.

There are different aspects of business growth and development. One faction may wish to apply technology to change its business as quickly as possible, while another may prefer to proceed cautiously and methodically, moving only after research and through using a well-tested methodology. Which is correct? The classic answer is “It depends.”

For bounded processes or projects, developers using Agile, or incorporating improvement techniques such as Lean or Six Sigma, may deliver successful projects quickly. However, in the opinions of many BPM practitioners, pre-IT planning may be required from senior management, along with skilled, expert consultant assistance.

The former group offers enthusiasm and technological skills. The other, more cautious group offers experience and intimate company business knowledge. In my opinion, BPM, to be most effective, requires the latter, longer perspective.

For larger and more encompassing projects, consistent planning and oversight, across both time and organizational scope, will be needed to produce broad and lasting corporate value. So, it is the range and scope of the chosen efforts which will determine which style best reaches the desired outcome. In military terms, you can move a Platoon quickly, but to move an Army takes more time and effort. It is not just the sum of the platoons.

Another consideration is: “Should we move through incremental continuous improvement, or through a major redesign? Again, it depends. Much of the current development literature emphasizes how to do the transformation the “fast” way. This article will recommend the Process Redesign approach for the broader, more encompassing methodology for longer lasting results.

Understanding

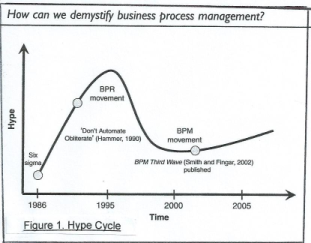

In their 2008 book, John Jeston and Johan Nelis (J & N) “Business Process Management …” (1/), they provided a chapter on the “Understand” section of their book. Early (on Page 5) they set the stage with the illustration, “Hype Cycle”, (2/) without numeric dimensions, only curves: Please see Figure 1 below.

This compact figure shows progression with a hump, peaking in mid 1990s, with Michael Hammer and James Champy’s “Reengineering the Corporation” book. By 2000, the hype had tapered off, as Smith’ and Fingar’s book, ”BPM Third Wave” provided more practical activities. Later books, such as Jeston and Nelis’s noted here, continued with a more useful way to proceed in BPM without the massive collateral damages as were expressed through Hammer’s approach.

In their framework, though, a most telling step, offers what they call Understand. The difference is they highlight that it takes time to perform a reasonable analysis. They express the needs on multiple levels, from the top Executive view of strategy and goals, on the middle Redesign level of metrics, simulation, and modeling, and on the lower Support level of adequate documentation and reporting. In the context before computerization, they explain why, to use a food analogy, “It takes time for the roast to bake.”

By simulating the “as is” steps, through communicating and holding workshops together with subject matter experts (SMEs) and by speculating about remedial actions and fleshing out details – it occupies time and energy. Separating productive from non-productive work – to be improved or eliminated – also occupies actual time to accomplish:

- Synthesizing the results from lower level analyses –

- Percolating up to the staff of the executive level –

- Moving in parallel on both redesign process level and management level.

While the redesign level deals with the transactions, volumes, costs, and even qualitative values such as complaints – key summaries flow upward – these are compressed to accommodate the scarce time available to the C-level executives and staff; who must absorb the essential details and actualize the corporate direction. Higher levels may also profit from surveys, productivity trends, competitive analysis, and other components also passed upward.

To illustrate by just one aspect of their analysis, they present a “People Capability Matrix” (3/), which may be expressed within functional business areas, and are given numeric ratings needed for future growth. See Figure 2 below, (“1” – essential skills, “3” – desirable skills). On the vertical axis, the processes are shown, and on the horizontal axis, actual performance skill level values required are noted to accomplish the processes’ objectives. The intersection, analyzed after an “as is” assessment of current skills and gaps, may improve results through training or reinforcements.

Reducing complex areas into a two-dimension matrix may help the executives zero in on the weaker areas, and help them to conceptualize how to focus training to the potential problem areas. Note that attention to the current state of the enterprise components often may not be considered for development activities. (An alternative too often chosen, in my judgment, is just to replace the current employees by consultants and start anew from scratch. In that case, much accumulated knowledge is thrown away.)

Lastly, with the “as is” analysis completed, innovation opportunities can be evaluated and prioritized. Other aspects, such as outsourcing, process elimination and “quick wins,” may be evaluated with efficiency and effectiveness. Outputs such as reports evaluating the tasks, risks and gaps may also be summarized to recommend next steps.

The early stages of the “Understand ” process are in direct antithesis to Agile techniques, where Scrum, Epics, Daily Builds and other tasks imply that practitioners are building a system with very little fore-knowledge, (learning as they go), of the end product expected by the Customer. Often, the end-user customer may not be in the picture at all until after several iterations, while the sponsor acts as a surrogate for the customer. Much churning around and developing the Information Technology aspects will be expected, while the scope of the redesign may still be vague. In many cases, the enterprise may be accelerating time and increasing cost. Actual costs may not show up until after many iterations building unnecessary product components not requested or needed by the customer.

A 2002 study by the Standish Group illustrated that, from several reviews of products and systems, up to 45 % of built components are never used. The Understand process articulated by Jeston and Nelis goes far to avoid the waste of time, money, equipment and mental energy. The waste may be replaced by thoughtful analysis, imple-mentation, and documentation prior to computerization. For the larger redesigns managed through BPM, using the time wisely – in order to do it right the first time, to plan up front, and to proceed with senior executive understanding of input and decisions. This might appear overly cautious at first, but it will most likely yield real profitable results faster and cheaper, with less rework, when the right planning and sequencing are executed.

Once the development plans are set, there is no reason not to use Agile or other cyclical, rapid development styles to accelerate computerization. Initial time spent planning with senior management, though, will save cost and time in the execution.

Notes:

1. Jeston, John and Nelis, Johan, “Business Process Management: Practical Guidelines to Successful Implementations, 2 Ed, Elsevier, Boston, (ISBN: 978-0-75-068656-3), 2008, 498pp.

2.) ibid, p. 5; 3.) p. 145.