“We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” – Albert Einstein

In the 21st century, government transformation initiatives have become increasingly more common, rather than exceptional. Some ambitious public sector initiatives turn out to be at least partially successful, though many others do not. Even when transformation success is declared, the outcome is often plagued by significant limitations that must be dealt with for many years.

Operational differences between Government agencies and companies in the private sector have long been recognized. Though some government entities such as the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office are paid by the public for many of their services, most agencies face restrictions with regard to their ability to generate revenue, with ultimate control over their mission, goals, and objectives being held by publicly elected officials. Many Government agencies find that they are required to deal with increasing public demands for their benefits and services, for which there has been a significant rise in recent years, while operating with increasing constraints on public spending. Electronic services are now being used to help modernize the delivery of Government services, but the challenge of improving public services has not yet been fully met.

Taking into account all the potential benefits and challenges, the Obama Administration continues to press hard to accelerate of the implementation of “e-government[1]” to improve federal services. As with organizations in the private sector, Government agencies are undergoing a great deal of change as they implement (and learn to rely more on) new processes that are increasingly enabled by such innovative technologies. Internally, management hierarchies are disturbed, organizational boundaries become blurred, new learning needs and development opportunities can lead to reallocated status and merits, even as transactions become more efficient.

Transformation is not easily accomplished in any organization, and the cultural changes needed within the government agencies may be greater than those experienced by workers in the private sector. Many of the issues that arise are considered “soft,” which means that they are hard for Government leaders and managers to come to terms with. In many agencies the staff, in particular, are exposed to what must seem like shocking changes to their work environment.

Despite the many institutional factors that make transformation difficult to achieve in government agencies, there is another (seemingly benign) one that can appear to be an even greater obstacle to the success of transformation initiatives in the public sector – and that one has to do with the way project management methods, tools, and techniques are often used, which may not prove readily adaptable to the needs associated with orchestrating large-scale, enterprise-wide transformation initiatives. Such initiatives cannot be effectively managed by a Project Manager or Program Manager – or even a Program Management Office – as those functions are have been “traditionally” applied to less challenging programs and projects.

Indeed, many government agencies have been assigning FAC-PPM-certified[2] Project Managers[3] – in their attempts to comply with OMB direction – to do the job of (what the private sector would call) a General Manager.[4]

In the PMBOK Guide[5], in other books on project management, and in my own experience in having held both general management and program/project management positions, there is a clear overlap in skills and expertise required of general managers and project managers. Also in the publications and in my own experience, there are skills that project managers must have that distinguish project management from general management. Also, I have known general management types who were assigned program management roles, and many of them do quite well without being avid proponents of project plans, task dependencies, work break down structures, detailed scheduling, critical path analysis, earned value, risks, issues, etc.

Limitations of Traditional Project Management Practices

There are two fundamental reasons – both of which are touted by Agile development fans – why traditional project management (PM) methods, tools, and techniques are not what’s needed to assure successful outcomes from major enterprise transformation initiatives. The first has more to do with the way many project managers apply their PM competencies and skills – i.e., in a manner that can become too prescriptive for highly complex, large-scale initiatives. The second has to do with the need to readily adapt to the inevitable changes that occur, and do need to occur, as a transformation initiative is undertaken.

For much of the second half of the 20th century, the mental model for providing IT solutions to challenging business problems has been to divide-and-conquer, more or less as follows:

- Decompose a large set of problems into smaller, “digestible” pieces

- Separate and prioritize “needed deliverables”

- Separately manage the activities required to produce the “needed deliverables”

- Conquer the smaller problems by working on each piece individually, and building each “needed deliverable” separately

This approach has proven to work quite well from a risk reduction perspective, since the complexities of the larger problem set are, in effect, factored out of the “problem-solving equation.”

By focusing the solution approach on smaller, more manageable chunks of the larger challenge, the relatively risk-free “comfort zones” provided for the different teams assigned to tackle individual “frames” of what really amounts to – in many transformational initiatives today – a “video stream” capturing many moving components of an enterprise-wide transformation challenge, gives rise to a much greater risk that individual “deliverables,” when separately produced, may not add up to a sum that is sufficiently “greater than its individual parts” to adequately address (much less resolve) the much larger, fast-moving problem set. There is also a risk that the many individualized deliverables might be overcome-by-changing-events, due to the amount of time it takes to develop, review, and approve each one as a separate deliverable. (Again, this is a critical element of the Agile-development case, which is becoming increasingly popular today.)

The decompose-the-problem-into-more-manageable-chunks approach to solving enterprise-wide business challenges – which may cater, by the way, to the propensity of some Government managers to “project-manage” their way through every transformational endeavor – can reinforce the dubious notion that the enormous amounts of energy poured into the delivery of a thousand point-solutions will culminate in a stunning flash of enlightenment at the end of the transformation tunnel.

What leads to disappointment more often than not, when the transformation timeline expires, is the collective failure to remember that the disaggregation of the components of any highly complex problem space, for the purpose of micromanaging the numerous bits and pieces of the needed solution, does not guarantee that:

- All of the problem’s actual subcomponents have been discovered and/or adequately addressed

- The relationships among the known subcomponents are thoroughly understood

- The aggregation of the multitude of delivered point-solutions has been (or can be) adequately tested against the “requirements” of the problem space – which in every case, will not have remained unchanged during the intervening time period.

Unfortunately, the project-management approach to working through the challenges posed by transformation initiatives today, combined with the Government’s traditional solution acquisition practices, may lead to more stove-piped IT solutions[6], rather than fewer, and to larger numbers of automation “silos.[7]”

Dealing with Change, as Enterprise Transformation Initiatives Take Hold

Traditional project management considers change and rework as the most undesirable aspects of solution development and implementation. Project managers are expected to severely limit, even prevent, unanticipated changes through exhaustive upfront planning, design, and carefully detailed specification. Conventional wisdom holds that if change occurs as a project is executed, then the front-end planning and documentation efforts must have been insufficient. Traditional solution development techniques advocate a step-wise development process that starts with a complete understanding of “requirements” and then progresses in an orderly manner from the establishment of needed foundational capabilities through the addition of middleware tiers, and finally, to the integration of user-accessible features and functions.

Agile project management, on the other hand, views project failure as the most undesirable outcome of solution development or implementation. It holds that requirements cannot be completely understood in advance – or that, to take the time required to fully understand the requirements in advance of design and development is not cost effective –, and that changes are to be expected and managed, rather than avoided. Accordingly, Agile-advocates consider planning, design, and specification beyond the minimum essential to start solution development and implementation to be wasteful. They want to focus on the early on delivery of useful working features and functions to one or more customers as soon as possible, as supporting capabilities are development and installed just-in-time, to support early adopters of the features and functions of the eventual solution set.

Unless they are very short, and extremely simple, projects do in fact change, no matter how well each might have planned in advance. In the case of major, enterprise-wide transformation initiatives, the environment surrounding them is always subject to change. Not least because they typically span multiple years, such endeavors are always subjected to budgets that can change from year to year.

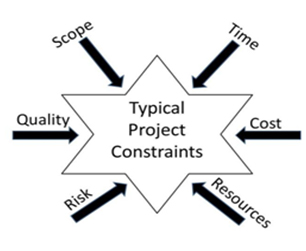

When customer demand for an agency’s services fluctuates over time, sometimes in distinctive cycles, resource needs are likely to be impacted. Schedules will need to change in unexpected ways as well, especially when one agency depends on another for source operating data – as the VA depends on DoD to deliver the military health records of Veterans in a timely manner. Yes, even the scope of projects will need to be adjusted occasionally, to deal with unforeseen circumstances (whether or not they should have been anticipated).

Even if such a shifting operational environment could somehow be avoided altogether, another form of variation would still affect enterprise transformation initiatives and their embedded projects. Each project team learns as it progresses and really should leverage the lessons being learned along the way. As new (or enhanced) features, functions, and services become incrementally available to users on any given project, they and the developers or implementers and their customers, managers, and other stakeholders become ever more aware of the project’s emerging impact on business operations. That reality includes a growing awareness of the project’s apparent limitations as well as other previously unforeseen potentialities, and how users will want to more effectively interact with it – all of which insights can only be realized as more exposure to the project is gained. All belatedly encountered discoveries, whether individually or collectively, will inevitably drive changes to a given project or sets of projects, or perhaps even to the entire transformation initiative itself (e.g., in the event that an especially impactful, enterprise-wide security vulnerability is exposed). Stuff happens, and leaders and managers must deal with change as it occurs, both responsively and responsibly.

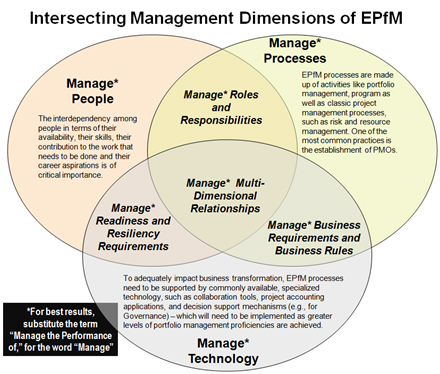

The complexity of enterprise-wide transformation initiatives requires that they be guided, directed, and influenced – not really managed – by the disciplined application of interlocking Strategic Planning, Program Planning, Budget Planning and Execution, Performance Management, Transition Management, and robust Governance processes, all exercised in concert across the enterprise, pursuant to an Enterprise Portfolio Management (EPfM) framework like the one depicted below.

For those unfamiliar with the term Enterprise Portfolio Management (EPfM), let me start with a bit of a definition. EPfM embraces several other more commonly known terms such as portfolio management or project portfolio management (PPM). More expansive than portfolio management and PPM, which have been most-often associated with IT in the past, EPfM (though it includes IT investments) offers more of a decision support process that facilitates enterprise-level strategic planning, strategy management, and transformation management.[8] EPfM can also be used to optimize strategic decisions related to discretionary investments including research and development, capital expenditures, and operational innovations, etc.

The EPfM methodology appeals to leaders with a preference for managing multiple investment and other transformational initiatives from a single, enterprise-wide perspective. This more centralized approach, and resulting ‘single version of the truth’ for project and portfolio information, provides the essential transparency of performance needed by senior managers to not just monitor progress versus the strategic plan, but also to more directly influence the achievement of “corporate” strategic goals and objectives.

The most important business drivers of EPfM can be summarized as follows:

- Optimize the interaction of following critical knowledge areas across the enterprise:

- Strategic Management

- Enterprise Governance

- Performance Management

- Communications Management

- Enterprise Risk Management

- Prioritize the right projects and programs: EPfM can guide decision-makers to strategically prioritize, plan, and control enterprise portfolios. It also ensures the organization continues to increase productivity and on-time delivery – adding value, strengthening performance, and ultimately improving bottom-line results.

- Eliminate surprises: Portfolio project oversight provides managers and executives with a process to identify potential problems earlier in the project lifecycle, and the visibility to take corrective action before they impact financial results.

- Build contingencies into the enterprise portfolio: Flexibility often exists within individual projects but, by integrating contingency planning across the entire portfolio of investments, organizations can have greater flexibility around how, where, and when they need to allocate resources, alongside the flexibility to adjust those resources in response to a crisis.

- Maintain response flexibility: With in-depth visibility into resource allocation, organizations can quickly respond to escalating emergencies by reallocating resources from other activities, while calculating the impact this will have on the wider business.

- Accomplish more with less: For organizations to systematically review project management processes, while cutting out inefficiencies and automating workflows and to ensure a consistent approach to all projects, programs, and portfolios while reducing costs.

- Ensure informed decisions and governance: By bringing together key project collaborators, data points, and processes in a single, integrated solution set, a unified view of project, program, and portfolio status can be achieved within a framework of adequate control and governance to ensure that all projects consistently adhere to business objectives.

- Extend best practices across the enterprise: Organizations can continuously vet project management processes and capture best practices, providing exponential degrees of efficiency as a result.

- Understand changing resource needs: By aligning the right resources to the right projects at the right time, organizations can ensure individual resources are fully leveraged and requirements are clearly understood. EPfM also allows an organization to optimize project capacity at any point in time.

The Case for Implementing EPfM

Still a relatively new approach to facilitating “corporate” strategic decision-making, EPfM provides Agencies with the ability not only to successfully complete more of their transformation-enabling projects, but also to more accurately align all their ongoing and planned projects with strategic goals and objectives, to deliver greater business value to their customers. This allows an enterprise to assess its performance against its publicized strategic objectives, while effectively mitigating the risks associated with investing public resources in the important business of government.

EPfM is designed to account for the costs and benefits of all of an organization’s programs and projects by continuously monitoring, evaluating, and improving the performance of its entire portfolio of enterprise resource investments. By using EPfM to aggregate all of its investments, a government Agency or Department is in a better position to ensure that it invests in the right projects, that it has the operational capacity – i.e., sufficient people, processes, “systems,” and facilities – to ensure the successful execution of all projects, to maintain the ability to absorb the impact of the changes resulting from the many projects, and to always understand whether the business is realizing the benefits expected from each of the projects. By institutionalizing its ability to accurately and realistically assess the performance of projects relative to these criteria, an Agency can readily apply accepted risk management techniques to all of its investments.

The task of developing and maturing an organization for portfolio management isn’t easy. Programs and projects must be constantly subjected to effective oversight, and the portfolio manager must be seen inside the organization as change agents, who stand ready to act as “conductors,” available to who help teams meet their respective goals — not as just as overseers, relegated to reviewing schedules and reviewing reports. With the implementation of EPfM, however, schedules can be adjusted to reflect critical paths and no longer driven by annual budget cycles. Portfolio managers can be empowered to devise creative solutions to resource-constraint problems. Because the EPfM method provides a stronger sense of the relationship between project execution and business benefit, managers can readily scale projects while still delivering measurable value.

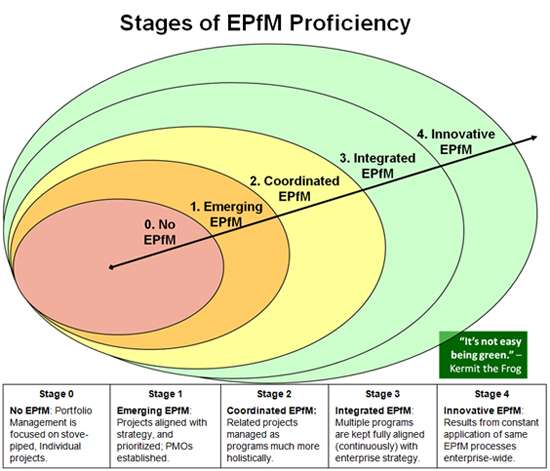

As an organization gradually improves and matures its EPfM capabilities (as illustrated below), its managers are able to restructure the way they manage the enterprise portfolio of all significant investments. With greater proficiency in the application of EPfM methods, an Agency can better evaluate an report its overall performance (in Annual Reports to Congress, for example) for external accountability purposes.

By demonstrating the actual linkages between enterprise-level strategic goals and the (aggregated) returns being realized from all of its resource investments in programs, projects, and initiatives aimed at achieving those goals, an Agency is much more capable of providing a clear view of the relationships that exist between the many localized causes and their collective, strategic effects.

Given reliable information about actual outcomes, executives and senior managers can make evidence-based determinations as to whether some projects should be eliminated (or modified), because they’re not found to be directly aligned with enterprise strategy.

Once portfolio managers are able to provide an aggregated view of enterprise investments, Agency leaders begin to rely on them to help business unit managers understand whether their investment levels are sufficiently planned and executed, to meet their own objectives. As a result, new projects can be initiated to close the gaps that get exposed through the EPfM process. In addition, an Agency can institute periodic reviews with program managers and business sponsors to discuss apparent gaps in strategic alignment and to continually reassess whether the portfolios maintained by individual business units continue to be fully aligned with “corporate” goals and objectives. Inevitably, the focus for business unit managers and program (and project) managers will be shifted away from the traditional practice of doing what had been seen as necessary to secure funding, to one of being accountable for results.

One of the keys to success is closing the loop back to the EPfM process owners at the completion of each project. By making business unit managers accountable for their impact on enterprise-level, strategic goals and objectives, an environment is created where resource investments will be considered from that pint forward, in terms of their expected contributions to mission success. The process makes the process owners and the project implementation team an effective partnership.

Further, the analysis of costs-versus-benefits will no longer be conducted only when projects and programs are reviewed for inclusion in the enterprise portfolio. EPfM will ensue that assessment becomes a series of ongoing events over time, and one that benefits from refined numbers, new metrics, and follow-on reviews of each project’s benefits. The dynamic nature of EPfM will help to ensure that an Agency approves the right projects (while defunding non-performing projects) at the right time.

The Bottom Line

By implementing the EPfM methodology, Government agencies will be able to focus on enterprise portfolio optimization as a primary means of delivering greater business value, both strategically and tactically, by optimizing their enterprise resource investments (e.g., introducing new assets, retiring obsolete ones, making modifications to others, etc.), while institutionalizing an enduring evidence-based strategy management process. As greater performance proficiency is achieved with the application of EPfM methods, agency leaders and senior managers will become better equipped to neutralize the complexities and the challenges of their enterprise-wide transformation initiatives – which can then be dependably guided, directed, and influenced by the disciplined application of interlocking Strategic Planning, Program Planning, Budget Planning and Execution, Performance Management, Transition Management, and robust Governance processes, all exercised in concert across the enterprise in the never-ending struggle to achieve mission goals and objectives.

[1] The basic drive towards e-government lies in the hope of achieving improved service quality and cost savings in service by the same means. It is based on the premise that, if business processes of an Agency are to be improved to deliver greater value to the customers, then information systems should be more tightly aligned and integrated to better enable the business processes of government.

[2] The Federal Acquisition Certification for Program and Project Managers (FAC-PPM) is governed by the April 25, 2007 Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) Memo on the Federal Acquisition Certification for Program and Project Managers Representatives. This policy outlines the education, training, experience, and continuous learning certification requirements to be certified as a project and/or program manager in Federal civilian agencies other than the Department of Defense (which has its own certification process). This certification program is based upon a competency model of performance outcomes that measures the knowledge, skills, and abilities gained by program and project managers through professional training, education, job experience, and continuous learning.

[3] Project management is defined here as the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to a range of activities in order to meet the requirements of the particular project – defined as a temporary endeavor undertaken to achieve a particular aim

[4] General management is defined here to simultaneously involve management of multiple aspects like design/engineering, technical support, logistics and infrastructure support (including IT), procurements and acquisitions, human capital services, and requirements development in a business unit or enterprise

[5] A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) is a book which presents a set of standard terminology and guidelines for project management. The Fifth Edition (2013) is the document resulting from work overseen by the Project Management Institute (PMI). The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) which assigns standards in the USA, assigned it (ANSI/PMI 99-001-2008) the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers assigned it IEEE 1490-2011.[1] for project management to PMI guidelines.

[6] Well integrated IT systems facilitate a more efficient and effective delivery of value to the customer. However, many IT configurations within too many government organizations are still relying on standalone applications, each with its “unique” presentation layer, business processing logic, and database. These stove-piped applications were built over the past two or three decades and were typically aimed at automating paper-based processes and designed to improve operations within one department-level business unit. Today, at least a generation (or two) later, departmental boundaries are different, and, more significantly, the systems are being made accessible by the public via electronic services through multiple channels, e.g., a call center or public web commerce portals. Government IT organizations face enormous challenges with trying to improve cross-functional business processes, providing accurate online information, and/or supporting multiple presentation devices.

[7] Organizational silos (as opposed to technology stovepipes) may be defined as groups of employees that tend to work as autonomous units within an organization. They show a reluctance to integrate their efforts with employees in other functions of the organization. The effect has the propensity to exist throughout an organization, or between Agencies (even between those belonging to the same Government Department), resulting in division and fragmentation of work responsibilities within the larger enterprise. Departments and business units can fragment into even smaller silos based on strong personal bonds, and areas of commonality that differentiate groups of employees from the rest of their department. Silos are a common occurrence, as they exist to a greater or lesser extent in most organizations

[8] The main distinction between project or program management and EPfM is a focus on meeting tactical versus strategic goals. Tactical goals are generally more specific and short-term than strategic goals, which emphasize long-term goals for an organization. Individual projects and programs often address tactical goals, whereas EPfM addresses strategic goals.