“All you need is the plan, the road map, and the courage to press on to your destination.” – Earl Nightingale

If you are a government program or project manager, let’s say in the IT solutions (or services) delivery business, you’re probably devoting a lot of thought to the long term view of how you plan to deliver on the promise of your product(s), solution(s), or services(s) – even as you grapple with the day-to-day challenges, risks, and issues that inevitably arise to frustrate your best laid plans. I suspect that you’re also maintaining some form of a road map for each of your projects, to highlight the many intermediate goals that need to be accomplished along the way – perhaps feeling frustrated at times by the need to maintain all that information on a single, fairly intuitive page.

Road mapping is often seen as a straightforward exercise of listing projects and aligning them with business priorities. In reality, the process should involve a lot of collaborative effort with numerous stakeholders[1].

I don’t know about you but my experience has been that a road map can quickly morph into a tangled clutter of blocks, arrows, annotations, corrections, post-it-notes, marginal squiggles, and footnotes, some of which were meant to capture unanticipated detours, delays, or other unintended deviations from (or additions to) the plan. When closely contemplated, though it might depict where the project is headed (and where it’s been), it may prove to be all but incomprehensible today, – perhaps even to some of the members of a project’s team.

To keep your road map under control, its purpose needs to be kept in mind

Your road map is supposed to be a visual representation of your long-term plan for success. It is also important to remember what it’s not – i.e., neither a Gantt chart, nor a detailed release plan. Instead, it’s intended to provide a high level view of how your outcome will be achieved, in what steps or phases, and how that outcome will contribute to achieving your organization’s business-goals and objectives, which will in turn, help your department or agency achieve its governmental mission.

Government agencies need to learn how to become more responsive to emerging changes in their operating environments. Many of them are starting to recognize that, to improve the business of government, their legacy processes and IT systems must be modernized. Given the current climate of increasingly constrained budgets, federal agencies are being driven to find ways to get more done with fewer resources. They need to be using more strategy-execution road maps as part of a robust strategy management framework, to provide guidance and direction on business and technology changes to stakeholders.

Vision is not the Road Map; it’s the reason for having Road Maps

A strategy road map provides a visually intuitive plan – with strategic priorities – for realizing a vision of future outcomes. While most government organizations are inclined to produce road maps, the reality is that traditional road maps are not always effective in practice. In many cases, the road maps are little more than Gantt-like charts that do not prove to be adaptable to change, when unanticipated circumstances or operational conditions arise. Perhaps the most common challenges encountered with the “conventional” use of road maps can be characterized as follows:

a) Typically, road maps have not provided business context, nor have they purported to explain reasons for change: Whether technology-, architecture-, business-, strategy-, or project-related, road maps often indicate what needs to be done rather than the reason for doing it a certain way. A business owner, for instance, is probably more concerned about making a contribution to agency priority goals than about the rollout of a specific technology solution. Without the business-strategy-execution context, a misaligned solution set may not be readily apparent.

b) Weak collaboration leads to lower confidence levels in what’s conveyed by many road maps: In the context that the term is normally used in our business, a road map is but a metaphor for a plan. By focusing only on the road map itself, without paying adequate attention to the significance of what’s needed to strengthen the mapping process (e.g., pertinent data, data analytics, and business context), the collaboration needed to create or update a road map can be easily overlooked by relevant stakeholders. What many agencies fail to understand is that the collaborative progression of building and maintaining a road map is far more valuable than the resulting product, which merely serves to memorialize that process.

c) Inadequate integration with strategic execution limits leaders’ flexibility: In the absence of closely integrated strategy execution processes and constant awareness of agency priority goals, government decision-makers are not well positioned to make timely decisions in response to emerging changes in their operating environment. As agency leaders strive to improve their ability to execute on strategy, success can only be measured in terms of their ability to execute. To significantly improve performance, they need to be able to rely on event-driven strategy-execution road maps.[2]

Learn how to effectively develop and use multi-purpose Road Maps

Various forms of road maps are being used in government agencies for a variety of purposes. Some are focused on individual projects, others relate to the evolution of architecture, and some may support portfolio management goals or capabilities-development objectives. It is important to ensure that meaningful relationships are established among those multi-purpose road maps – and that those relationships are maintained over time. This can be more readily accomplished by assuring that each road map, regardless of type, features the following, essential characteristics:

- Clearly Identified Outcomes (Prioritized) – to provide the business context for what’s reflected in each map, outcomes derived from objectives, performance goals, achieved strategy alignment, or successfully mitigated risks, etc. should be depicted – and associated with specific scenarios or certain anticipated events.

- Strategies for Achieving Projected Outcomes – broadly stroked strategic themes, underlying the agency’s business model, that indicate what must be the focus of activities performed in pursuit of declared outcomes. For example, an agency may decide to significantly increase its customer service response times in a sustained effort to attain higher customer satisfaction levels.

- A Schedule for Delivering Projected Outcomes – depending on agency needs, the window of time covered by a given road map may be as long as five years or as short as a few months; the point is to set (and meet) firm expectations for outcome delivery (though intermediate milestones should be planned at relatively frequent intervals within lengthier delivery periods, to assure adequate status and progress accountability).

- Stakeholder-tailored Execution Sequencing – road map content that effectively reflects the sequence of anticipated activities and events, communicated in a manner that stakeholders can comprehend[3].

- Outcome-affecting Dependencies – these dependencies need to be highlighted not just initially, but also updated for the duration of the end-to-end timeline for each road map.

Switching for the moment to the analogy of an old fashioned (trip-orienting) road map, which serves as a guide by illustrating various routes to get travelers to their desired destination, a road map of that type doesn’t tell anyone where to go, and it doesn’t suggest a rate of speed typically, for getting from one location to another. That’s for the traveler to decide. The value of using that map has more to do with increasing one’s awareness of available options, than with establishing a specific route to be taken. Whether digitized for electronic viewing or printed on (unwieldy) paper, the virtues of an ordinary road map are appreciated by most road “warriors.” As a given trip is undertaken, such a road map informs many choices that can be made along the way, in response to unanticipated roadblocks or poor traffic conditions, etc. In this scenario, a good road map enables a different, informed choice to be made at nearly every encountered cross-road. Such intermediate choices can be made without abandoning one’s original destination, though a traveler would presumably factor in any “costs” to be incurred by departing from the initially planned path.

In the government’s IT-enabled operational environment, event-driven strategy-execution road maps can enable a leader to make adjustments when unanticipated circumstances – such as a significant budget cut – compel his or her agency to change course, or to extend the timeline(s) for achieving some of its strategic outcomes. By updating dependencies among road maps when such choices have to be made, agencies can maintain much-needed clarity of purpose, while continuing to assure strategic alignment – and informing meaningful discussion among affected business and technology stakeholders. Such dynamic mapping abilities highlight the key steps needed to maintain an agency’s shared vision, especially when changes are communicated in ways that all stakeholders understand.

Enhance Strategy-Execution by Aligning Road Maps within a Framework

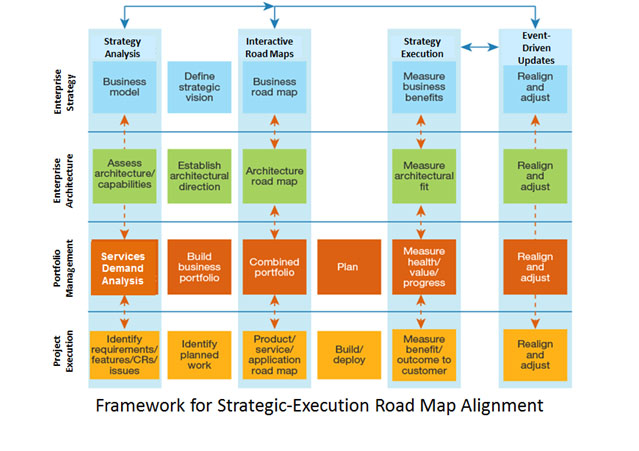

The use of dynamic road maps enables an agency’s leaders to better leverage output from strategy management activities, such as analyses of alternatives, solution selection, needs prioritization, and implementation/performance assessment. A structured but iterative and collaborative road map maintenance capability helps to quickly turn changed priorities into a sequenced set of deliverables that can be reflected on multiple, event-driven maps. The following Framework for Road Map Alignment illustrates some of the relationships to be maintained among strategy execution maps.[4]

[1] Translating business strategies into strategy-execution road maps involves more than developing a list. Each initiative must be reconciled with an overall schedule. One needs to evaluate alternative approaches, identify and leverage synergies among initiatives, and dedicate resources to the highest-value opportunities. Yet, the dynamics of the business operations and project related conditions require ongoing readjustment and review. The result is clear but flexible road maps that can be shared with all stakeholders.

[2] Event-driven artifacts are updated when a triggering event occurs (or is imminent), e.g., when a project milestone is reached, or when portfolio investments are rebalanced. Static road maps tend to be rarely updated, perhaps because they aim to monitor only major events. With “living” road maps, a greater number of significant event triggers can be actively monitored, thus allowing decision-makers to react to unanticipated changes more rapidly, with greater confidence in the information available to inform their decisions.

[3] Road maps that contain too much information (or provide insufficient business context), whether dynamic or static, will prove to be of little value or no to stakeholders. Successful road map planning decomposes complex projects/portfolios/investments into subsets and ultimately into elements on a road map. When an individual element changes, the impact of that change is visible on the potential outcome and/or internal timing of the more complex project/portfolio/investment.

[4] Adapted from Forrester’s Strategic Planning-to-Execution Framework, February 2014