Recap

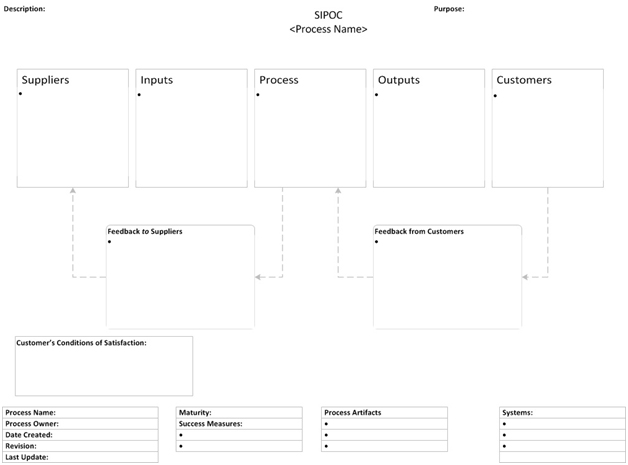

In the last article, I described a project to capture and catalog the major cross-functional processes within a 7-department business unit. The article provided an example of a modified Supplier, Input, Process, Output, Customer (SIPOC) diagram, discussed the problem statement, and described the steps we took to get buy-in from the Sr. Management of the business unit.

This time, we’ll explore the modified SIPOC in greater detail to illustrate how it is created, and how it can be used. We’ll discuss the catalog that is the inventory list of the SIPOC processes that have been diagrammed.

The SIPOC Diagram

A blank SIPOC diagram is shown below. I was introduced to this format in 2005 by the Orion Development Group, who refers to it as a type of System Map. They used it as part of their standard document set, and also taught this format in a class given in conjunction with Pepperdine University Graziadio School of Business and Management. Over time, I have modified the diagram for various purposes and used it to good effect to focus a work group’s attention to why they do what they do.

We’ll examine the elements to describe their purpose.

Description: This is a brief description of the process being diagrammed. Provide sufficient information for someone outside of the business unit or work group to recognize the work being performed.

Purpose: Provide a reason that this process exists. I find that the easiest way to do this is to answer the question, “Why does our company believe this process is important enough to expend resources and materials on it?”

Process Name: Each process should be given a short, descriptive, and unique name.

Suppliers: List each vendor, internal department, person, or business unit that provides input to the process.

Input: What do each of the suppliers provide? Think of this as the raw material being transformed within the process. It’s easy to list the raw materials and components in a manufacturing or physical process, such as the hoses used in the carburetor assembly. People sometimes get stumped when the output of the process is intangible, such as a report or repeating software release cycle. For these, list specific raw data and information that is needed to produce the end products. Requirements might be an input to the software release cycle, for instance. Note that processes are repeatable and ongoing. This diagram is not appropriate for project level efforts, such as new software. But if your release cycle is done periodically and is repeatable each time, it can be considered a process.

I’ve seen support processes included in the Supplier and Input list, such as governance, HR support, policies, etc. These elements that are likely common to all processes might be better depicted at a higher level, such as an Enterprise or Business Architecture diagram. Like all things process, this decision is situational.

Process: The process section is a very high-level list of what’s done to the inputs that transforms them into the outputs of the process. This might include three or four bullets about the general activities that take place, but should not include the discrete steps that would appear in a swim lane or simple process flow. You might list “Assemble widgets” and “QA widgets”, but those would be at the what level, not the how.

Outputs: This is what you’re producing and must tie closely to the Purpose statement you have done. An alternate description for any process is to transform inputs to outputs. There might be a single output, or several, but all should have the same underlying suppliers, inputs, process, and customers.

Customers: The individual, department, organization, or external entity, or category to which the outputs are delivered. For a manufacturing process, you may be passing on a component to the next department or assembly line, or you may be naming the category of “Purchasers of Widgets”.

Feedback to Suppliers: This is a critical component that is often not included on a simple swim lane diagram. How do your suppliers know that what they’re providing is of sufficiently high quality, timely, and complete enough for you to produce a high quality and complete product in a timely manner? Formal feedback, provided on a regular schedule, is the key to continuous improvement to your process. This is a good time to consider whether you have established these loops with your suppliers, and work in partnership with them to set them up.

Feedback from Customers: How do you know that what you are providing is of sufficiently high-quality, timely, and complete enough for your customers? Is feedback always solicited from those receiving the output of your process? What is done with that feedback? Your customers’ satisfaction should be solicited with each delivery, and having metrics on this feedback is key. If your customer is not the ultimate user of the product or component, one question to ask is how they gauge their customers’ satisfaction, and partner with them to make the final users’ delight your common goal.

Conditions of Customer Satisfaction: This concept was introduced to our business unit last year by Sage Alliance Partners as part of their Value Driven Work model, and seemed an important enough component to add to our SIPOC diagrams. Soliciting ongoing feedback, as above, is important, but really understanding the spoken and unspoken requirements of your customers requires in-depth conversations with them. Realizing that things change frequently, having the conversation once isn’t sufficient. You may be getting regular feedback that what you’re providing is of high-quality, but what if it’s no longer exactly what they need or expect? Have these conversations frequently in an informal, collaborative venue, in person if at all possible. Surveys are great, but what’s being left unsaid is as or more important than their stated requirements.

One note about the relationship between these elements: you needn’t expect a single supplier connected to a single input, connected to a single process step, and nor are your outputs linear, one-to-one relationships. There may be many-to-many among any of these elements. You may also find that there are times your suppliers are also your customers – think about an entity providing you with requirements, and you delivering the final output to the same entity.

Consider the above, and in the next installment we’ll talk about how these are used to create the final Process Catalog.