Business architecture ties together a diverse ecosystem that represents your enterprise from a wide variety of perspectives. These include strategies, tactics and goals; business units; semantics and rules; capabilities, value chains and processes; projects and initiatives; and customers and suppliers. These business “artifacts”, along with the relationships among these artifacts, are the essence of business architecture. The complexity of most organizations is such that the business ecosystem cannot be readily visualized by the individuals managing and working within that ecosystem. By representing business artifacts in the business architecture metamodel, the ability to visualize complex business ecosystems becomes a reality.

Many organizations are concerned about visualizing their as-is and to-be business architecture for a variety of business reasons. The path from point A to point B is never clear when you have no GPS readings for where you are now or where you are going. The as-is business architecture allows you to envision the root cause of critical business issues that management is demanding be addressed. Envisioning the to-be business architecture creates a clear vision as to how to correct these root cause issues. The transformation plan between A and B creates the roadmap of initiatives and projects that allow you to achieve that vision. So, how can we accomplish this when there are so many artifacts in play? The answer is the business architecture metamodel.

First, we should examine just what management and analysts want to see before jumping into the metamodel. Executives like simple pictures. Directors and managers want more detail. Project planners and architects require even more detail. The key here is that regardless of how you want to zoom in and out of the business architecture and which parts you need to see at a given point in time, the underlying structure must support business planning and deployment requirements for a wide variety of business scenarios. Executive views, typically pictures, remain more art than science. These pictures are abstractions that summarize the underlying details and reality at a very high level. Every business architecture team should have someone that has the ability to help executives see the big picture. But even in this case, the details provide the foundation for the executive view.

Vice presidents, directors and managers are more likely to want to see visuals that they have worked with previously. This may include balance scorecards, capability models, operational views, organizational and supply chain models, and so on. As with executive views, this requires understanding a big picture view that can be used to produce these visuals. In these examples, tool vendors must step up to take the underlying information in the metamodel and provide the visualizations. To date, few vendors have taken up the mantel to tackle this visualization challenge from a business architecture perspective. Part of the reason for this is that there is no agreed upon metamodel of how all of the business artifacts tie together. There are, however, best practices that are being driven towards a standard by the standards community.1

The metamodel can take on many forms depending on how it is to be used. The important point is that any organization and any team within an organization will likely want to see a variety of views of the business ecosystem at any given point in time. Business artifacts must be organized in such a way as to allow the greatest degree of flexibility for the largest audience without compromising the integrity of the information that is being shared. In addition, metamodels should share a common set of semantics when deployed across different business units. For example, the term “division” should mean the same thing regardless of where it is being used to define organizational structure.

Let’s assume that you have several customer call centers servicing an overlapping customer base and that the enterprise as a whole has been steadily losing customers – for unknown reasons. Management will want to diagnose the situation in order to craft a solution. This requires understanding which business units, across certain divisions, are supporting certain customers for various products and services. It also requires identifying common processes that each call center uses, the semantics that define their understanding, the rules that govern their actions, and where processes begin and end from a cross-functional perspective. A business architecture metamodel, structured correctly, allows management to understand the root cause of a problem and objectively discuss ways to address these issues.

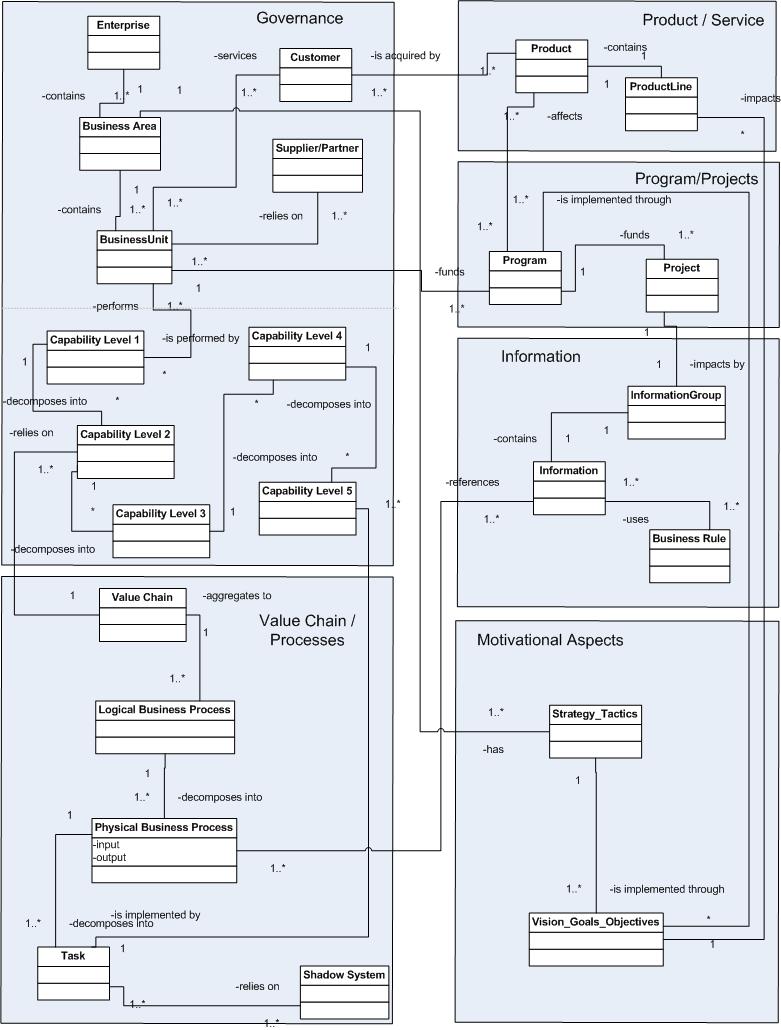

An initial project, such as the one in the above example, provides a starting point to gather and assimilate meta-data on relevant business artifacts. This allows the metamodel to be populated through real projects that address immediate management priorities. Initial and ongoing business projects provide the means by which to build out the information knowledge base of your enterprise. As this occurs, subsequent projects will have less information to gather. There is no right or wrong metamodel, only what is right for your enterprise. I have included a sample snapshot of a data model below that has been used in practice and has served as a discussion metamodel for work going on in the standards community.

Figure 1

The use of a metamodel such as the one depicted above varies depending on what tools you own and your business architecture roadmap. Some organizations have used this type of model to guide the customization of their architecture modeling tools – some of which come with over 250 artifacts and an endless number of relationships. Other organizations have deployed the model in a database, in anticipation of the time when vendors begin to offer off-the-shelf solutions for business architecture. The tools should provide prepackaged business architecture meta-views along with visualization tools that allow business professionals to understand the enterprise ecosystem. I should note here that use of the underlying metamodel is limited to a small number of individuals who need to assimilate and maintain business architecture related information. Executives, directions, managers and analysts would never see the metamodel, only the information produced through various visualizations.

The simplest deployment of the sample data model could be in an Access database, although most organizations would put it in a more industrial strength database such as Oracle. Ultimately, business artifacts need to be stored and managed in a standards-based business architecture tool that automates much of the visualization required by the business community. The bottom line is that understanding and transforming the business architecture ecosystem requires a multitude of holistic views to be assimilated and presented in a wide variety of ways. This will not be accomplished in spreadsheets or in Word documents, where information is lost and cannot be assimilated or managed in useful ways.

1 Object Management Group, Business Architecture Working Group.