1. The Real World

Architects (i.e., building architects) have been grappling for a long time with the challenge of making architecture accessible to the general public, both as a form of artistic expression and as a practical discipline rooted in utilitarian considerations. What they have found is that most people equate “architecture” with “buildings” – i.e., the final product – without giving much thought to the creative conceptualization and design work which long-precedes the actual construction. Exceptions to this rule are famous buildings such as the Guggenheim Museum in New York or the Sydney Opera House, where the otherness of the edifice itself suggests that both artistry and engineering must have had a hand in the design and planning of the construction.

Much like Business Architects, building architects don’t generally advertise their services publicly. Rather, the way architecture firms earn their keep is by competing on contracts by submitting models for evaluation and selection. This business model still dominates the industry, however, over the past six years, things have started to change. A company called ArcBazar, located in the U.S., made waves in 2011 when they opened the first online direct-to-consumer market targeting individual and business consumers looking for design services and architects willing to offer a design solution. The reaction from the architecture community was swift, with one architect going as far as to state that ArcBazar would be “aiding and abetting the illegal practice of architecture.” The public, nevertheless, caught on to the model and to-date hundreds of projects have been posted for submissions by individuals and businesses; more than 8,000 clients architects and designers from around the world have registered to compete for these projects. ArcBazar’s business model has given rise to similar ventures (such as CoContest in Europe), which together have pushed the envelope in democratizing architecture by breaking down barriers between architects and consumers. These days, crowdsourcing sites such as Kickstarter allow consumers to both crowdfund and co-create public benefit projects such as parks, urban art installations, and even innovative housing solutions.

2. The Virtual World

In the world of IT, tapping into the wisdom of crowds has been common practice for a while. Through code-sharing repositories such as GitHub, learning portals such as Stack Overflow, and platforms such as TopCoder, software engineers and developers participate in crowdsourced or open source projects, many times for little or no remuneration other than the satisfaction of creating better tech.

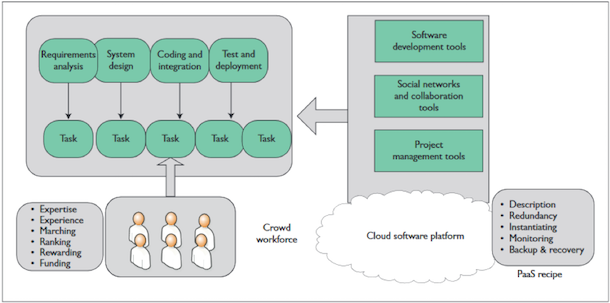

Crowdsourcing the development of large, complex information systems is a complex endeavor in and of itself, and reference architectures such as the one shown in the graphic below (see Figure 1) have been created to guide the design of the collaborative ideation process. Such architectures take into account the multiple players involved – the customer, the worker, and the platform – as well as the main processes performed – idea collection and selection, task decomposition, coordination and communication, planning and scheduling, quality assurance, knowledge management, IP management, and rewards or remuneration i . The crowdsourcing reference architecture in Figure 1 includes System Design as one of the distinct tasks distributed to the “crowd workforce”, which is another way to say that the architecture of the system under development is itself built through crowdsourced contributions.

Figure 1: Reference architecture for cloud-based software crowdsourcing (excerpt)

Some in the industry are making the case that good architecture in crowdsourced software development does not happen spontaneously, but rather that it needs to be orchestrated by an “architecture-owner” whose mission is to organize those in the crowd workforce with architecture experience (aka “worker-architects”) into a team tasked with creating the architecture vision for the project iii. The architecture vision includes information on the system boundaries, the quality scenarios and attributes, the development platform, the main architectural patterns and principles, and the main domain models. Once the architecture vision is established by this architecture team, the worker-architects would then join the software development teams and evangelize the architecture vision throughout the development process. As the project progresses, new architectural requirements may be identified; these requirements would serve as additional guardrails to the development teams as they make architectural decisions, develop proofs-of-concept, and develop, integrate and test the solution.

3. The Corporate Business World

Building Architecture, Software Architecture and Business Architecture can be thought of as cousins residing in different dimensions. While Building Architecture focuses designing structures in the real world and Software Architecture does the same for the virtual (information) world, Business Architecture deals with defining and optimizing the structure of the corporate business world. Therefore, when a trend – such as crowdsourcing – starts gathering steam in one or both of these cousin-disciplines, we Business Architects ought to pay attention. If done right, leveraging the knowledge and collective wisdom of everyone in the organization can be the key to business transformation.

But, there are challenges, and foremost amongst them is the fact that the “crowd workforce” in the organization is made up of employees at various levels of professional maturity and experience, who bring very different views of what works or doesn’t work for the business. Their views and inputs in matters related to the internal organization structure, processes, internal controls, workforce expertise, business model and growth patterns could be vastly different and, if not guided and filtered, could turn the organization’s business architecture into a veritable tower of Babel.

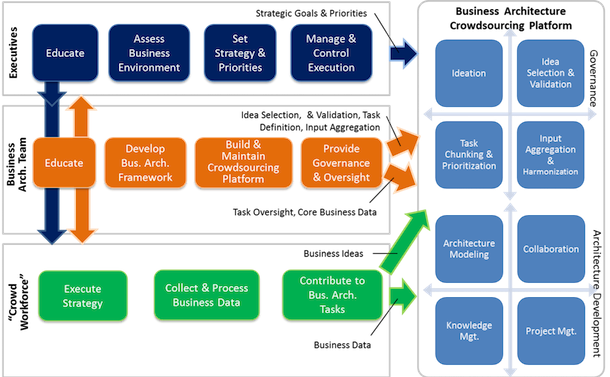

Similar to the reference model for software crowdsourcing presented earlier, business architecture crowdsourcing should be based on a reference architecture that ties the players to the architecture-building tasks through the means of a tool platform and a defined governance layer (as illustrated in Figure 2). The reference architecture would be planned and operationalized by the Business Architecture team and their executive champions; once in place, responsibility for continuously enriching the business architecture would be delegated both upward and downward of the Business Architecture team, with the Business Architecture team serving as a change control board and promoter of standards and methods. As employees’ level of familiarity with the business environment, business strategy, business patterns and best practices gradually increases, so will their level of engagement and their confidence in proposing organizational improvements, business process improvements, and improvements in the types and quality of the information ingested and exposed by the organization. Eventually, the crowdsourcing of the business architecture will generate a virtuous cycle of business innovation and renewal and become a true game-changer for the organization.

Figure 2: Reference architecture for Business Architecture crowdsourcing

As highlighted in the graphic, education is a key ingredient to making business architecture crowdsourcing work. The executive layer would be responsible for educating both the Business Architects and the crowd workforce on the business strategy – main concepts, goals, priorities, environmental factors – while the Business Architecture team would educate both the executive layer and the broader workforce on principles, methods and best practices in business artifact creation. While the outreach and education process would not be trivial, the benefits of an engaged workforce, both in the practical and figurative sense, would have a multiplying effect on the employees’ job satisfaction, quality of work, productivity, customer-centricity, innovation levels, and ultimately on the profitability and growth of the organization.

[i]Software Architecture for Collaborative Crowd-Storming Applications, by Nouf Jaafar and Ajantha Dahanayake, 2015.

[ii]Cloud-Based Software Crowdsourcing, by Wei Tek Tsai, Wenjun Wu, Michael N. Huhns, 2014. Published by the IEEE Computer Society.

[iii]Crowdsourcing Software Architecture: The Distributed Architect, by Stefan Toth, 2017.