“To more fully realize the benefits of behavioral insights and deliver better results at a lower cost for the American people, the Federal Government should design its policies and programs to reflect our best understanding of how people engage with, participate in, use, and respond to those policies and programs.” – President Obama

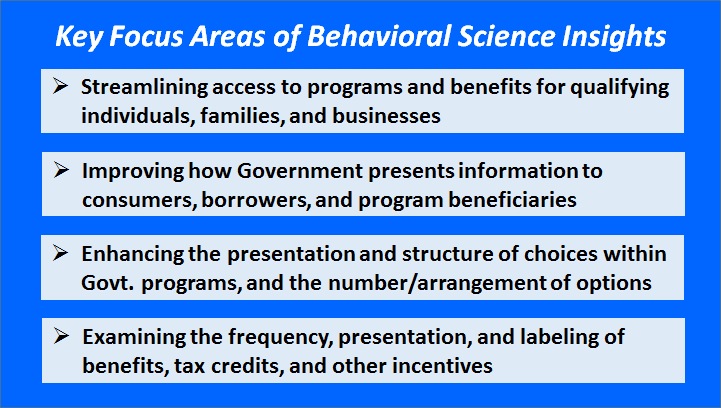

With the issuance of Executive Order 13707 (“Using Behavioral Science Insights to Better Serve the American People”) in September 2015, the President encouraged federal departments and agencies to identify policies, programs, and business operations where the application of behavioral science perceptions may lead to significant improvements in public welfare and the outcomes (and cost effectiveness) of public programs – so that strategies can be developed to apply lessons-learned from behavioral science to the operational effects of those policies and programs, and then evaluate the impacts of applying the resulting strategies.

Executive Order 13707 also encourages federal departments and agencies to recruit behavioral science experts to join the Federal Government (as needed) to achieve the directive’s goals, while also strengthening relationships with the research community to better use empirical findings from the behavioral sciences. The Order established a Social and Behavioral Sciences Team (SBST) – working under the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), which is chaired by the Assistant to the President for Science and Technology – to provide agencies with advice and policy guidance to help them implement the policy objectives outlined in the President’s directive. The SBST aims to do this by redesigning public services, drawing on ideas from the behavioral science literature. Its members are also highly empirical; they test and trial their ideas before they are scaled up. This enables them to understand what works and (just as importantly) what does not work.

Behavioral insights, which draw on research into behavioral economics and psychology to influence choices in decision-making, have revealed how behavioral economics and other behavioral sciences shed light on decision-making processes. These insights can do much more than improve how individuals make important personal decisions. They can also help leaders make better decisions about major policies—and ensure those policies effectively improve society. And, by focusing on the social, cognitive and emotional behavior of individuals and institutions, they suggest that even subtle changes to the way decisions are framed and conveyed can have big impacts on behavior.

The Need for this Innovative Approach, to Improving Government Services

The federal government administers a broad range of programs on behalf of the American people: financial aid to help with college education, social insurance programs and tax incentives to support retirement security, health insurance programs to assure access to healthcare and financial safeguards for families, disclosure obligations to help people secure more dependable mortgages, and others. But, Americans are the better served by such programs (and the business processes that enable them) when the program can be readily accessed, while clearly offering simple options and intuitively descriptive information.

Programs not designed with these factors in mind run the risk of adding additional costs that go beyond lost time and human frustrations. Research from behavioral science shows that seemingly minor barriers to consumer engagement (e.g., hard-to-fathom information, difficult applications, or imperfectly differentiated choices) can cause programs to work ineffectually for people they are meant to serve.

For example, one behavioral science study found that a complicated application process for financial aid was more than just irritatingly stressful; it had the effect of discouraging applications for aid, and led some would-be students to delay or even pass up college altogether. Fortunately, behavioral science can not only detect features of programs or processes that can act as barriers to customer engagement, it also provides decision-makers with indications of how those obstacles can be eliminated.

That same behavioral study showed that streamlining the process of applying for financial aid—by providing families with online application assistance and enabling families to automatically fill parts of the application form using information from their income tax return — increased the rates of both aid applications and college enrollment.

When business policies are influenced by behavioral insights (i.e., research findings from behavioral economics and psychology about how people make decisions and act on them), the ensuing returns have proven to be significant. Since the federal government applied insights from the financial aid study to make the process of applying for federal student aid less difficult, college has been made more readily accessible to millions of Americans.

The Pension Protection Act of 2006, which required the automatic enrollment of workers in retirement savings plans, was based on behavioral economics research demonstrating that switching an enrollment system from an opt-in to an opt-out one dramatically increases participation rates. Since the implementation of this business policy, increases in automatic enrollment (and automatic escalation rates) have led to billions of dollars in extra savings by Americans.

Early Results from SBST Efforts

From the SBST’s initial formation in 2014 — based in the Office of Evaluation Sciences at GSA — its members began working across the federal government to apply findings and methods from the social and behavioral sciences to help the business policies, programs, and operations of government improve services to government customers. In its first year, the SBST partnered with more than a dozen federal agencies to design and test the impact of behaviorally-informed interventions within targeted programs and business policies. SBST Fellows and associates have since worked to creatively translate insights from the social and behavioral sciences into concrete recommendations, while working closely with agency partners to structure and implement experimental trials capable of assessing the relative effectiveness of proposed interventions — using swift, thorough, and low-cost verification methods. Most of the changes applied by the team, as it turned out, were relatively small – e.g., involving a text message, rewording a letter, personalizing an email, etc.

Over its first year, SBST concentrated on executing proof-of-concept projects where behavioral insights could be embedded directly into government programs at a relatively low cost and lead to immediate, quantifiable improvements in program outcomes. In building its initial portfolio of work, SBST centered on projects in two areas where behavioral science had great potential to increase process performance, and where impacts could be quickly demonstrated:

- Streamlining Access to Government Programs — Working closely with agencies across the federal government, SBST used behavioral insights to expand program reach and promote greater retirement security, increase college access, connect more workers and small businesses with economic opportunities, and improve health outcomes. To promote retirement security, for just one example, the team looked at participation in the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), a workplace savings plan for federal employees. SBST and the Department of Defense (DoD) launched an email campaign that sent approximately 720,000 unenrolled Service-members one of nine email variants, designed using behavioral insights, to notify recipients of the opportunity to participate in TSP. Compared to no message at all, the most effective one increased the rate at which Service-members signed up for TSP by nearly 100%. Emails informed by behavioral insights led to more than 4,900 new enrollments and $1.3 million in savings – within just 30 days after the emails were sent. DOD is now scaling up the effects of this intervention by sending periodic emails shaped by behavioral insights to Service-members about the benefits of TSP.

- Improving Government Efficiency — Many measures of government efficiency are contingent on decisions made, and actions taken, by individuals such as program administrators, benefit recipients, and contractors. The SBST applied behavioral insights to enhance program integrity, conserve operational expenses, and identify programs that could be made more efficient. To increase program integrity, for instance, the team examined ways of verifying and validating sales figures being self-reported by sellers of products and services to the Government, SBST and the General Services Administration (GSA) restructured an online data-entry form to place a signature box at the top of the page used to confirm the correctness self-reported transactions. Since suppliers pay a fee to the Government based on those reports, the inclusion of the signature box led to nearly $1.6 million in additional fees collected within just three months. Based on this result, GSA made the change to that particular form a permanent one.

Bottom Line

In nearly all cases it has looked into, and there have been too many to mention here, the SBST has been able to generate evidence about the effectiveness of applying these behavioral insights using randomized evaluations — the gold standard of evidence among policymakers and social scientists. Based on results from early SBST efforts, a number of federal agencies are making lasting changes to program design and administration. The SBST plans to continue to working with agencies to take the lessons from these early successes and scale them, so that more Service-members, more students, more farmers, and more Americans generally, can benefit from a Government that makes full use of the insights that behavioral science can offer. To do so, the SBST will help build capacity within agencies to effectively and independently apply behavioral insights to their programs and business processes.

Finally, SBST results further demonstrate the potential of behavioral insights to strengthen policy reform efforts in the future. If prompting enrollment at key points can increase participation in a retirement savings plan, what might that mean for the design of the process to access to that plan? If an email can help applicants choose a student loan repayment program, what does that suggest about the way that set of choices should be structured? Through relatively small changes to program administration and business processes, the impact of SBST-projects points to broader opportunities for decision-makers across the federal government to rely on these and other behavioral insights to better serve the needs of many more Americans.