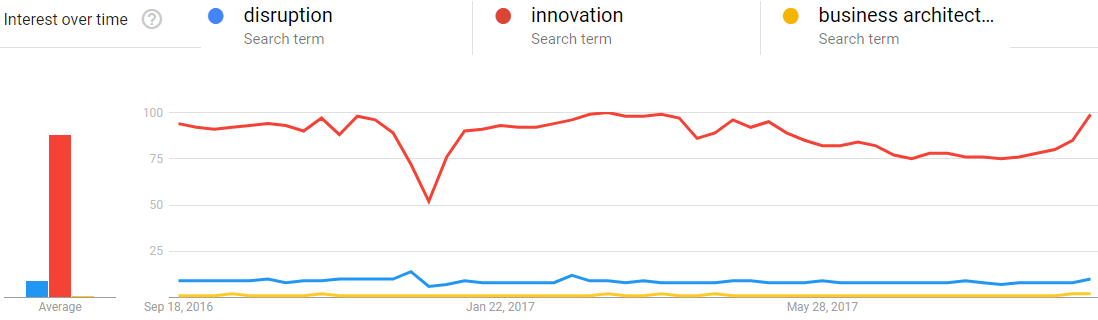

Over the past decade, the Business Architecture community of practice has built a firm foundation of methods, practices and tools that allow organizations to map their place in the business world, assess the viability of their capabilities, and chart a course towards their future. And yet, Business Architecture still has a long way to go to permeate the public consciousness. In fact, while concepts such as change, disruption, and innovation have fired up the imagination of entire industries, Business Architecture’s public brand as a game-changer has drawn more muted reactions, as the Google Trends diagram below starkly demonstrates.

Figure 1: Google Trends graph (dated 9/16/2017), keywords: disruption, innovation, Business Architecture

The Complex Organization

This article posits that the traditional methods comprising the standard Business Architecture canon assume an orderly, slow-changing and relatively predictable business environment. An environment devoid of any major external or internal upheavals; an environment that can “wait” for the Business Architect to, well, architect. In other words – it assumes an environment which doesn’t exist in real life.

In real life, business organizations are subject to continuous change which occurs not linearly, but rather in fits and spurts, as a result of external events and stimuli which impact the organization in various ways, and in turn trigger internal reactions and responses of lower or higher intensity. Thermodynamics (the branch of physics that deals with the relationship between heat, work, temperature, and energy in a system) stipulates that in a closed system, the level of disorder can only increase as such systems tend to move from ordered behavior to more random behavior. The measure of disorder in a closed system is called entropy (from the Greek entropia – “changing” or “transformation”). While a business organization is an open system rather than a closed one – since it exchanges information (energy) and physical resources (matter) with its environment – the concept of entropy still applies albeit in a modified form, as a measurement of the system’s probability to change.

| The Viable System Model

One of the first comprehensive models to describe an enterprise’s organizational structure as a viable, autonomous system, organized to meet the demands of its environment and survive in a changing context, was the Viable System Model[1], proposed by cybernetician Stafford Beer in 1972. Mr. Beer used this model to advance a mathematical method for calculating the entropy of such a system, and to propose a set of areas critical to the success and sustainability of an organizational system. These areas include culture, leadership, strategy, internal communications, and internal controls, amongst others. As entropy builds up in the organization (usually as a result of environmental pressures and internal disruptors), emergent behaviors can manifest in any of these areas. Whether such emergent properties are positive or negative in nature has a profound effect on the direction the company takes and its survivability. Innovation is an example of a positive emergent behavior in an organization. At the negative end of the spectrum, an organization may slide into toxic practices such as theft and industrial espionage. |

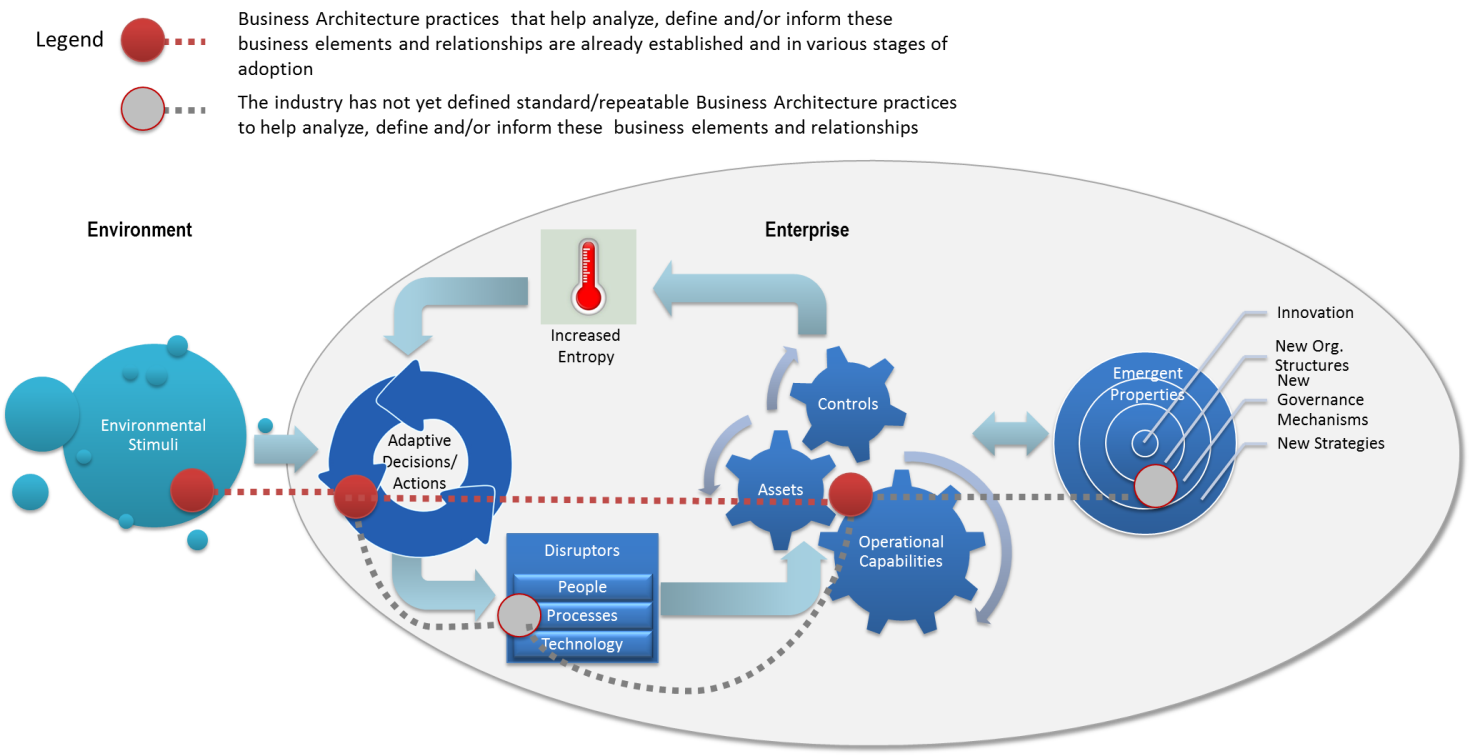

In fact, the concept of entropy is highly applicable in explaining the evolution of business organizations. Much like a coral reef, an ant colony, or a slum in Kolkata, studies have shown that a business organization is a complex, adaptive, social system composed of hierarchically organized components – such as the Board of Directors, the executive management, business units, Finance, HR, project teams and so on. The organizational units that make up the business are interdependent, in constant and non-simple interaction with each other, have distinct functional, spatial and temporal boundaries, and are influenced by their surrounding environment. The enterprise as a whole and within its parts has organizational self-awareness and, through its many components, organizes itself for survival and growth. As the environment in which it functions becomes increasingly complex – whether as a result of globalization, political changes, resource shortages, or shifts in consumer preferences, to name a few examples – the enterprise and its many components must also change and adapt. The adaptive decisions and actions made by the organization in response to such external stimuli yield internal responses that can take a variety of forms – organizational realignments, functional realignments, right-sizing, introducing new technologies, adopting new processes, or hiring the kind of people who ‘can make things happen’ – in other words, disruptors. Such disruptors create friction, friction increases the level of entropy in the organization, and the rising entropy generates the conditions under which new behaviors can arise. These new and unexpected behaviors are referred to as ‘emergent properties’, and they can be of different types – new business strategies, novel governance models, cutting-edge technologies and skills, or innovative processes such as co-creation.

New Vistas for Business Architecture

The complexity inherent in business organizations is ripe with possibilities for architects to build on the existing Business Architecture body of knowledge to create new, innovative offshoots of the discipline that can more flexibly support the nonlinear, rapidly-changing nature of business. Correlating the business concepts described so far into an enterprise-level view (below) makes it easier to spot the areas where Business Architecture practices have already caught and are yielding valuable insights to organizations, as well as the areas still off the beaten path for Business Architects.

This article recommends that Business Architects familiarize themselves with methods from adjacent domains such as strategic planning, management consulting and system engineering, and complement their traditional repertoire with practices and techniques suitable for the study of complex systems. A summary of recommended practices (and reading materials) grouped by the supported business concept is provided below.

1. Frameworks, practices and tools supporting the analysis of external, environmental stimuli

With the exception of the Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats (SWOT) analysis method and the occasional foray into Business Model analysis, the methods suggested may not yet be adopted by mainstream Business Architects. Leveraging such methods is essential in recognizing that a business system is an open system, constantly exchanging information and resources with its surrounding environment, and that actions and reactions within the business are driven to a large extent by its interaction with its immediate environment.

| Applicable Framework, Practice or Tool | Suggested Reading |

| SWOT analysis

Business Model Generation analysis PESTLE analysis Five Forces |

Linking Business Models with Business Architecture to Drive Innovation (A Business Architecture Guild Whitepaper).

Osterwalder, Alexander; Pigneur, Yves. Business Model Generation, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013. The Five Forces (Harvard Business School, Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness). |

2. Frameworks, practices and tools supporting the analysis of adaptive decisions and actions

In order to adapt and grow, business enterprises contend with a wide array of decisions – from long-term, strategy-setting decisions, to immediate-term pivoting, investment or divestment decisions. Such a broad spectrum of decisions requires a correspondingly varied repertoire of methods and tools to support sound, informed decision-making, ranging in complexity and level of abstraction from the traditional capability mapping and planning to the innovative use of predictive modeling.

| Applicable Framework, Practice or Tool | Suggested Reading |

| Capability Mapping/Planning

Red Ocean/Blue Ocean Value Mapping Decision Modeling Bayesian Probabilistic Modeling |

Capability-Based Planning (The Open Group, TOGAF® 9.1, Part III: ADM Guidelines & Techniques, Capability-Based Planning).

Kim, W. Chan., and Renée Mauborgne. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 2005. Value Map Overview (Professor Ken Homa, Georgetown University) An Introduction to Decision Modeling with DMN (Decision Management Solutions, 2016). Various Approaches to Decision-Making (S. Roy, Decision Making and Modelling in Cognitive Science, DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3622-1_2, Springer India, 2016). |

3. Frameworks, practices and tools supporting the analysis of the organization’s assets, controls and operational capabilities

Architecting the assets, controls and operational capabilities[i] of an enterprise has been the bread-and-butter of Business Architects and Enterprise Architects for some time now, and there is a substantial body of literature describing the relevant practices, methods and tools – one of the best exemplars being the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge® (BIZBOK® Guide) developed by the Business Architecture Guild. This article recommends complementing Business Architecture methods with elements of Enterprise Architecture and decision modeling practices.

| Applicable Framework, Practice or Tool |

Suggested Reading |

| Business Process Modeling

Information Modeling Organization Modeling Enterprise Architecture frameworks Decision Modeling |

Business Architecture Body of Knowledge® (BIZBOK® Guide) (The Business Architecture Guild).

TOGAF® 9.1 (The Open Group). The Zachman Framework (John A. Zachman). An Introduction to Decision Modeling with DMN (Decision Management Solutions, 2016). |

4. Frameworks, practices and tools supporting the analysis of business disruptors

The methods suggested below have traditionally been the domain of academics, researchers, engineers, mathematicians, statisticians and data scientists. The Business Architecture practices of the future could leverage advances in these adjacent domains to rapidly model, simulate and assess the impacts of adaptive decisions and actions on the organization, identify gaps in the enterprise architecture stack, select the areas that can most benefit from a disruptive intervention, plan the disruptive intervention, and evaluate the probability and impact of potential outcomes.

| Applicable Framework, Practice or Tool |

Suggested Reading |

| System Dynamics Modeling and Simulation Quantitative Methods Performance Engineering Predictive Analytics Machine Learning/Artificial |

The Analysis and Valuation of Disruption (Derek Nelson, Hill International, Inc., 2011).

Quantitative Analysis of Enterprise Architectures (Maria-Eugenia Iacob and Henk Jonkers, Telematica Instituut, the Netherlands). Demystifying Disruption: A New Model for Understanding and Predicting Disruptive Technologies (Ashish Sood and Gerard J. Tellis, 2010). How to Recognize, Prioritize and Respond to Digital Disruption (Gartner, Inc. – requires subscription).

|

5. Frameworks, practices and tools supporting the analysis of emergent properties such as innovation

“Innovation is the endogenous result of the system dynamics: it does not fall from heaven, as standard economics suggests. Innovation is the result of the collective economic action of agents: innovation is a path dependent, collective process that takes place in a localized context, if, when and where a sufficient number of creative reactions are made in a coherent, complementary and consistent way. As such innovation is one of the key emergent properties of an economic system viewed as a dynamic complex system” (Prof. Cristiano Antonelli of BRICK[i]). As this quote suggests, planning for innovation requires a comprehensive analysis of the underlying causes and systemic conditions that make emergent properties such as innovation possible. To provide real support in identifying (or better still, predicting) emergent properties in the system, advanced Business Architecture practices will have to be developed to incorporate methodological and practical elements from the theories and methods offered here.

| Applicable Framework, Practice or Tool |

Suggested Reading |

| Complex System Dynamics Modeling and Simulation Quantitative Methods Predictive Analytics Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence Complexity Theory, Chaos Theory Models of Knowledge

|

What are Emergent Properties and How Do They Affect the Engineering of Complex Systems? (Christopher W. Johnson, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK).

Definitions of emergence (Vrije Universiteit, Brussels, Belgium) Innovation as an Emerging System Property: An Agent Based Simulation Model (Cristiano Antonelli and Gianluigi Ferraris, Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 2011) Localised Technological Change, Towards the Economics of Complexity (Cristiano Antonelli, Routledge, 2008) Prof. Ilya Prigogine’s works, particularly Order Out Of Chaos (1984) and Exploring Complexity: An Introduction (1989)

|

[i] As illustrated by the Business Architecture Guild, A Guide to the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge® (BIZBOK Guide®).

[i] S. Lovin, The Value Creation System (The Value Creation Blog, 2017).

[i] C. Antonelli, Localised Technological Change, Towards the Economics of Complexity (Routledge, 2008).