1. Approaches to ECE.

The change of such a complex system as Enterprise has to be considered at least from three perspectives:

- The philosophical equation of inevitable change.

- The business equation of embracing vs. ignoring change

- The human equation of Enterprise change success.

2. The Philosophical Equation

Change is one of the most important philosophical concepts of all. Generally, philosophical laws and forces are the most powerful in the sphere of reason, and, when correctly understood, provide equally powerful means to achieve practical results. They silently but relentlessly work in the background of each and every mind’s and life’s processes. The one who understands them wins, the one who use the term ‘philosophy’ sarcastically may regret it.

Arguably the most powerful philosophical theory of change belongs to Georg Hegel who considered spiritual changes in the form of ‘triads’, when the conflict between ‘thesis’ and ‘antithesis’ provokes change and finds its resolution in the form of ‘synthesis’ . For the last 200 years, this formula has proven itself to be correct every time any change in ideas has occurred, and each time has had an enormous, decisive practical impact. Moreover, it provided analysts with a mighty tool to predict the way in which not only ideas but also their practical implementations will develop.

There is an ideological change behind any practical one. So, there should be a theory of evolution behind every practical evolution of any objective system. Otherwise, we find ourselves in the darkness, able neither to predict its next steps, nor to explain the previous ones, nor even to comprehend the system’s current state. When we consider the Enterprise’s evolution from this point of view, as we did in, we should be able to derive the philosophical Enterprise Change Equation directly form Hegelian dialectics.

In the business sphere this equation points to the conflict between the level of development of the forces of production (in our case the number and scale of Applications) and the relations of production (in our case, Architecture, and Processes that support the Enterprise Business Model (EBM)) as the main catalyst of change. It states that inevitably raising the quantitative or qualitative level of the former must, at some point, be met with qualitative change in the latter.

This is the philosophical equation of Enterprise change. It is also a practical manifestation of yet another Hegelian law: the dialectic law of the transformation of quantitative changes into a new quality. Having been seriously and timely considered, this conflict can be resolved evolutionally; having been ignored, it can cause revolutionary cataclysms inside the system under consideration ( e.g., Enterprise), such as the loss of business sustainability and competitiveness.

3. The Business Equation

As applications of this general law for the case of an Enterprise, we can consider a relationship between EBM on the one hand, and quantitative parameters, such as a Number of Applications (NA) or qualitative ones, such as Available Technology (AT), on the other. Here are the possible scenarios, all ignoring the necessity of change:

- If the level of EBM’s complexity has risen, but has not been followed by necessary change in either AT ,or NA, or both, the support of EBM suffers and eventually fails;

- Likewise, increasing the level of NA and AF without changing the EBM means that the former increases do not bring new revenue while rising costs; in this scenario EBM also suffers;

- Now, the most practical and relevant scenario: if a change of EBM complexity has a quantitative nature but is supported by only quantitative change in NA and AF but not in Architecture & Processes that glue NA and AF together, the increased complexity in NA and AF will fail to make the necessary positive impact on EBM (or even make a negative one); thus, this scenario quickly becomes a variant of the previous one and also leads to the EBM’s struggling.

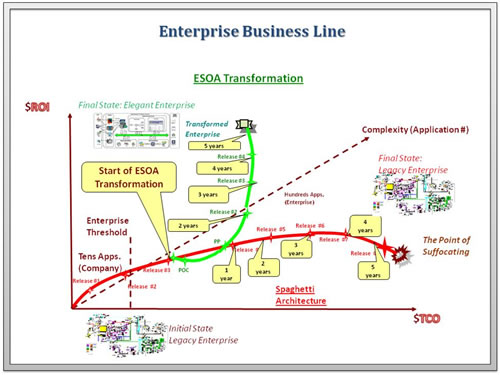

Let us try to illustrate these scenarios graphically. In theoretical physics there is a term ‘world line’ that describes a body’s trajectory in the four-dimensional space-time continuum. Correspondingly, let us introduce the concept of a ‘business line’ that will describe the trajectory of a company/Enterprise in the two- dimensional ‘business-time’ continuum.

As the axes for such a graph two well known financial parameters have been chosen:

- ROI – as an indicator of the ability of IT to generate revenue per dollar of investments;

- TCO – as an indicator of the investments into IT;

Figure 1 demonstrates how these indicators behave with the growth of internal complexity expressed in the number of IT applications.

|

Figure 1 The Business Equation of Enterprise Change.

It shows how slowing ROI at some point puts the Enterprise Management before a dilemma: Whether to realize the growing conflict between the artifacts’ complexity and the obsolete nature of the means of their realization, and start Enterprise Business Architecture Transformation (EBAT), or to ignore this conflict and continue ‘business as usual’. The two business lines for an Enterprise in Figure 1 correspond to these two scenarios. The red one shows how without EABT, despite the growing investments into IT (TCO), the ROI growth first further slows down and then becomes negative. The latter happens when Business/IT Legacy ‘spaghetti’ Architecture becomes so complex that attempts to change something inside it lead only to additional problems due to the infamous ‘ripple effect’.

On the other hand, the green ‘business line’ shows, after a very important and challenging but doable and short period of initial investments and adaptation, not only increasing ROI growth with lesser investments (TCO), but even continuing ROI growth with decreasing investments! The former happens at the Reuse/Replacement Stage of the effort and reflects mostly shorter time-to-production of ongoing projects due to increased reuse and easier replacement of functional components. The latter effect happens during the final, Consolidation Stage of the initiative, when more emphasis is placed on excluding all functional and informational redundancies. This stage requires moderate investments but soon brings substantial economy in maintenance costs of the excluded redundant components and systems.

A well-developed and defined description of the EBAT process may be found in Enterprise Service-Oriented Architecture Framework (ESOAF) . Some of the remarks on the graph in Figure 1 refer to this framework.

4. The Human Equation

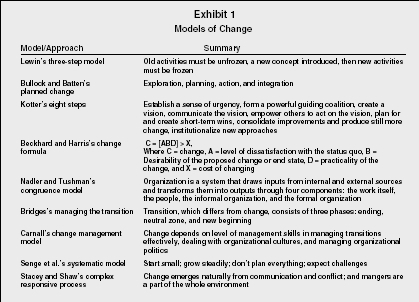

Having established that Enterprise Change is nothing but objective, inevitable, and fruitful, let us take a brief look at the current research landscape in the field of Change management. A summary of existing approaches can be seen in Figure 1, which has been published at.

|

Figure 2 Models of Change

As we see, none of the approaches, listed in Figure 2, declare and/or explains the inevitability , nature, and objectivity of change. A large-scale Enterprise-level change, which is very costly and highly traumatic by its very nature, simply cannot be justified without showing its inevitable character, as well as exploring the consequences of failure to change. From our point of view, the only well-formulated and practically relevant approach is that of Beckhard and Harris, which leads to their famous ‘formula of change’ (see Figure 2):

C = [A+B+D] > X

Equation 1. Beckhard’s and Harris’s Change Equation

This formula is absolutely acceptable for an Enterprise with one significant caveat: the human parameters of this equation, such as dissatisfaction with the status-quo of the system, desirability of the proposed change, as well as the ability to soundly estimate the practicality of the change of the system in question, depend heavily on the ability of the change stakeholders to identify their personal well-being with the well-being of the system. This is where Enterprise differs dramatically from lesser-scale systems. An Enterprise is so vast, functionally and geographically distributed, has such a federated Business Architecture that the only two organizational bodies whose members satisfy the aforementioned criteria are Upper Management (UM) and Enterprise Architecture (EA) teams. Other stakeholders’ teams might not possess the necessary level of understanding to correctly appreciate the ‘factors of change’. Hence, they could and they will show some level of unconditional resistance (R) to the change of the system beyond their comprehension, which we must add to our new, Enterprise-oriented change equation. The negative factor R can and should be compensated by a set of mitigating factors, applied by the main stakeholders UM and EA to the rest of them:

- E, which represents an educational and training package, intended to increase the stakeholder’s overall change preparedness and comprehension;

- M, which denotes the motivation package, intended to reward participation in change;

- F, which represents the clearly announced commitment of the UM to the change, which includes all administrative actions, necessary for its success.

The new, Enterprise-oriented Change Equation for stakeholders other than UM and EA, will combine the parameters from Equation 1 with the new, Enterprise-specific ones:

C = [A+B+D] + [E+M+F] > X+R

Equation 2. The Human Enterprise Change Equation