When introducing the Decision Model I frequently quote John Zachman’s classic gem “It occurs to me that once the underlying structure of a discipline is discovered, friction goes to zero! The processes (methodologies) become predictable and repeatable.” Every project in which we have implemented the Decision Model has seemed to bring further proof that – in the world of business logic or business rules, it seems to create a frictionless environment. We see “Ah ha!” moments time and again when people realize the simplicity to which their complex logic or business rules may be reduced by applying the model.

However, just last week, I was leafing through the book that Barb and I wrote on the Decision Model (The Decision Model: A Business Logic Framework Linking Business and Technology, Auerbach 2009) and realized that we have already evolved our practices in the use of the Decision Model quite significantly since the book was completed. Not in the basic theory – that seems to remain constant, whatever curved balls we throw at it – but in the practices involving implementing model. The processes that Zachman talks about seem amenable to quite a bit of tweaking.

It shouldn’t be that surprising. In the preface to the book we invoke Edmund Phelps, the great US Economist, and Nobel Laureate, when says that it is not necessarily the important discoveries, but actually the practical knowledge that is learned when implementing those discoveries – the “tweaking” that the practitioners are able to achieve – that is the cause of the great leaps in value in economy. So we see the elimination of friction due to the implementation of a theory that accurately reflects the underlying structure of the logic; but it is in the practice that we see refinements that bring about great leaps in productivity.

We first proposed the theory of the Decision – in an unpublished paper – just three years ago, and completed the first draft of the book over two years ago: the many redrafts and the publishing took care of the time elapsed since then. But all this while we worked with close clients to test and implement the theory. The results were very heartening. In chapter 7 of the book we detail a fictional case study that in large part was drawn from actual experiences with client engagements during this period.

It is now a year since we handed the manuscript to the publisher, and in this time our practice of the Decision Model has evolved very significantly. In this piece I would like to bring you up to date with one of the exciting new developments in Decision Modeling, the one that has had the most profound effect on our practice, and that is the Decision Model View.

Business rules, or business logic, in the enterprise can be very complex. If we consider one of the more challenging business rule environments, the nationwide, multi-line insurance company, we soon realize the nature of challenge. Such a company must operate in up to 55 different regulatory regimes, each with its own rules and practices, while at the same time managing business lines as diverse as property and casualty life, and perhaps health care, subdivided still further into many different lines of business and yet further orthogonally delineated into personal and commercial lines – which could be yet further divided in small to medium business, and large commercial and so on. Not to mention several possible specialty lines. And of course, this could be yet further complicated by having several different channels of sales. Business rules not only abound in this environment, but are segmented, sub-segmented, and cross-segmented in very complicated ways. While this may be an extreme case, it does represent the challenge that is faced in trying to model logic across any enterprise.

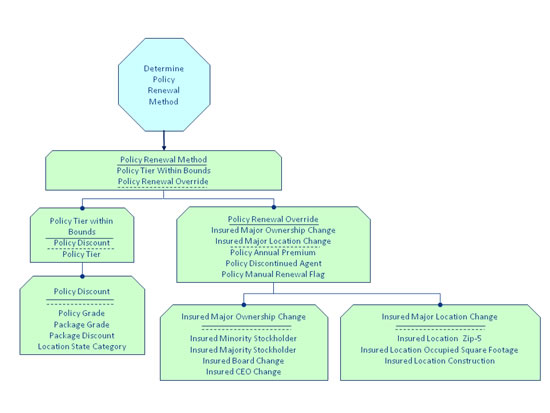

Take the model that is used in Chapter 7 of The Decision Model, and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Decision Model from Chapter 7

Adapted from: The Decision Model: A Business Logic Framework Linking Business and Technology, von Halle & Goldberg, © 2009 Auerbach Publications/Taylor & Francis LLC. Reprinted with the permission of the Publisher.

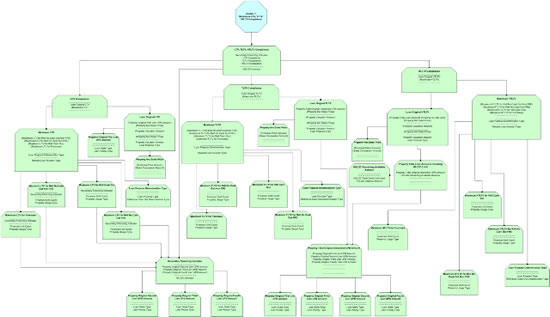

This Decision Model determines whether a policy is to be renewed automatically, or needs to be reviewed manually by an underwriter. The underlying logic (the business rules) evaluates several conditions that lead to this determination. Would, however, that it were always this easy. In the case of the multi-state, multi-line insurance company, there would be numerous exceptions and differences depending on the State, and depending on the line of business. It would be necessary to add many condition fact types to each of the Rule Families: at the very least, the fact types of State and Line of Business would have to be included in many; while fact type’s specific to the logic of each individual locality and line of business would also have to be included. Some of these added fact types may be derived, and be dependent upon supporting Rule Families, increasing the number of Rule Families. Each business rule that is specific to a State or group of States, or Line of Business would potentially add many rows to the Rule Families, increasing size and complexity and making analysis increasingly more time consuming. Assume that there are but two additional fact types per State, and two additional fact types per line of business, there could be a few hundred additional fact types, and many potentially many additional Rule Families. Figure 2 is an illustration of a complex Decision Model, demonstrating the challenge of such complexity. This is from an actual client’s enterprise Decision Model, but the resolution has been reduced to protect the business logic for client confidentiality.

Figure 2 Illustration of a Complex Decision Model

It’s not as if this is a Decision Model specific problem. It is the source of the difficulty of managing large bodies of complex business rules: they typically have a great deal of inter-dependencies, and without the Decision Model it is difficult to trace the impact of a one change across the whole rule base. This is what leads to the very high cost of developing and maintaining business rules. The Decision Model greatly simplifies this, but the question remains how to better manage the complexity of the enterprise model.

Thus notion of the Decision Model View. Put simply, the View is like looking at the Decision Model through a filter, just as one may look at a complex database through the filter of a SQL View to focus on just the data that is of interest at a given time. In fact, the Decision Model View is created by integrating relational model principles into Decision Model structures. Using this approach Decision Models are created, managed, analyzed and implemented as Views of the underlying Enterprise Decision Model. In fact our practice is to no longer manage Decision Models, but their Views; this is similar to the concept of never permitting application developers to directly address tables in RDBMS, but limit their access to Views only. This enables the Data Modeler to completely isolate and make changes to the schema without perturbing applications accessing the data.

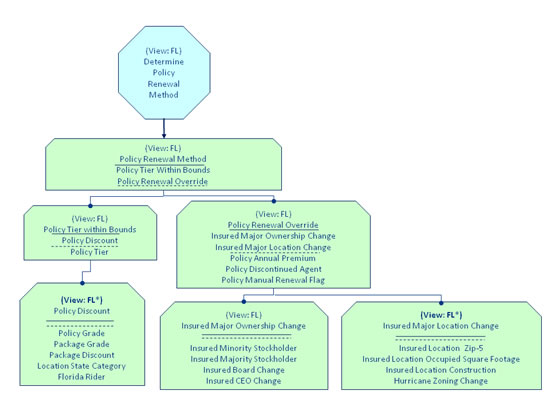

Figure 3 The FL View for Determine Policy Renewal Method

An illustration of the use of Decision Model Views is shown in Figure 3. Imagine that the Decision Model in Figure 1 has been expanded to a nation-wide insurance company with a great deal of State specific logic, extending the Decision Model accordingly. In Figure 3 the View is of one State only, Florida, thus filtering out all the complexity of all the other States. The Rule Families that have been modified from the Base View (the “Base” is the name of the default View of the Decision Model) are highlighted and marked with an asterisk. It can readily be seen that there are two additional Fact Types relating to Florida specific issues, Florida Rider in the Rule Family Policy Discount and Hurricane Zoning Change in Rule Family Insured Major Location Change. There may be a single View for each State or group of States. Views can also be compound: there could be a View for a State/Line of Business combination, such as a View of a particular Decision Model for Workmen’s Compensation for the State of New York.

Views bring a very great deal of agility to the Decision Model, enabling a generalized model to be made specific for a host of reasons: perhaps to customize the business decision for a given group of customers, or even individual customer; perhaps to provide for specific logic to be applied to a product group or range of products, and so on. Our early experiences with Views teach us that this is the future direction to pursue using the Decision Model.

To support Decision Model Views, the notation has been extended. This is illustrated in Figure 3: the View name is shown in both the Decision and the Rule Family shapes. The convention is to omit the View name when modeling the Base view, but to display the View name for all Rule Families, even those that are not modified in the View. Those that are modified by the View are indicated by an asterisk, and the View name is displayed in bold text. This way it can be seen at a glance which Rule Families are affected by the change. In the case of Rule Families that are redundant in the View, the Rule Family shape, Rule Family name and View name are displayed with no lines; this indicates that the Rule Family is omitted in the View.

The development of Views in Decision Modeling is an opportunity to solve problems inherent in modeling logic across complex domains, and a clear roadmap toward the higher levels of the Business Decision Management Maturity Model. Most importantly, it is proving itself in practice.