In a previous life I was in charge of management reporting for the pan-European logistics organization for Compaq. My team was responsible for monitoring and reporting the daily, weekly, monthly and quarterly performance and progress of the operations. We provided reports on shipments-to-date, invoices send, estimated shipments for the remainder of the day, week or month, order cycle time and average shipment lead-times, and on and on. None of these metrics would keep me awake at night or would cause heavy discussion on accuracy and validity of the metric. That was reserved for one metric: “Predictability”.

Predictability was our #1 metric for customer satisfaction. It also had all the characteristics of a badly chosen metric:

- No real ownership (read: accountability)

- Nearly impossible to root-cause

- Home-grown, thus no realistic benchmarking information.

- Multiple interpretations (shipped v. delivered, factory v. logistics)

- Everybody was impacted by it’s poor performance (as it was linked to profit share)

- And maybe most important: Unclear value to the customer

Recognize this type of metric?

A proper metric has an owner, it is meaningful to your customer (whether internal or external) and it has a proper definition. A metric like predictability never really improves and it becomes a curse to anyone that touches it. (My nick-name was ‘mister predictability’).

Nowadays I take a different approach on metrics. I use three basic rules in selecting metrics:

1. Use standards. I prefer metrics that have been tested by others;

2. Measure yourself the way your customer measures you

3. Only measure metrics that have an owner

So, what is this ‘standards thing’ you may ask. Let’s look at that logistics operation in Europe: clearly a supply-chain function with warehousing, consolidation and shipping as core activities. The recommend standard supply-chain reference framework with metrics is SCOR. I use SCOR whenever I need to look at the performance of a supply-chain. It provides me with 3 valuable things in the metric space:

- Standard metrics. These are pre-defined metrics; how is it measured

- Metric categorization. Metrics are grouped together based on the type of performance they represent (e.g. Reliability, flexibility, cost, etc).

- And very important a linkage to those processes that influence a metric’s performance.

The final benefit is the endorsement of approx. 2500 companies across all industries that these are metrics that are valuable to them. If you remember the problems with the predictability metric you can see the benefits of SCOR metrics: No discussion on how it is measured, a clear linkage to processes that may cause the poor performance and endorsements on the value of the metric itself.

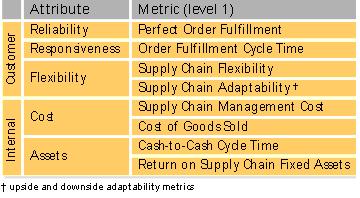

This table shows the SCOR performance attributes (I called them categories) and the highest level metrics. Levels in metrics indicate whether you look at the overall performance or on a detailed aspect of the supply-chain.

SCOR = Supply Chain Operations Reference, maintained by the Supply-Chain Council, www.supply-chain.org)

These level-1 metrics span the performance of the total supply-chain from procurement of the materials, through producing the product, to delivering and installing the product at your customer. If I want to focus on the customer then I will be directed towards, Reliability, Responsiveness and Flexibility. The importance of one versus the other is determined by industry competitive advantage for your company, or even more importantly how your customer measures you. My company’s choice would have been reliability (predictability indicated the accuracy of shipping or sometimes delivering against the day we promised we would ship or deliver).

What to do if company is not so standard? I recently worked with a military organization responsible for maintaining a fleet. Their core processes are maintenance, repair and overhaul to keep their fleet operational. In the SCOR language this is covered in the Returns processes. They had been instructed to “use the same metrics as the great supply-chain examples -like WalMart- do”. But however they looked at their operation the inventory metrics did not seem to make sense. My question for them was “How do your customers truly measure you?” The answer: The cost per flying hour. We found this to be very similar to the ‘return on supply chain assets’ metric in SCOR. My recommendation: Adapt the SCOR metrics to your organization. Replace a standard SCOR metric with your similar metric. But make sure you retain the linkage to the processes. This way you can root-cause the issues and design a permanent solution to your performance gaps later. Oh, and forget about ‘the WalMart metrics’ and start looking at how companies that operate similar processes to your business measure themselves. As an example: transportation companies maintain fleets (see, air and road).

How do you find the metric at the right level for your organization? If the metric is too high level it measures beyond the boundaries of your organization. The way to find the right level is to drill down until you find the right metric for your organization.

In this example, no level 2 metric is available that matches the need. Yet level-3 was too detailed. Therefore I consolidated the appropriate level-3 metrics to a new level 2 that does match my organization. By consolidation of level-3 metrics I retain the links to the processes (via level 3). Furthermore I already have some metrics that I can link to the departments within my logistics organization (faultless invoices for my billing department).

And that’s how I select a metric. 3 Simple checks make all the difference:

[ ] This is a standard metric (If not replace with a standard metric or start with standard lists)

[ ] This is how my customer measures me (If not don’t use it or if not exactly find the closest match)

[ ] This metric has an owner (If not decompose the metric the next level and test again, continue until all components have owners)