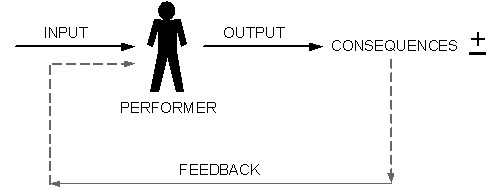

The human performance system (HPS) is a model that describes the variables influencing the behavior of a person in a work system. The HPS has been used by performance analysts and others for some 40 years to diagnose and even predict the likely behavior of human beings in given performance situations. The earliest version of this model was created in the 1960’s by Geary Rummler and Dale Brethower . Today, there are any number of versions of this model, but the original, shown in Figure 1, is still powerful and relevant to anyone interested in understanding or improving performance.

The model is based on several important tenets:

- Every organization is a complex system designed to transform inputs into valued outputs for customers.

- Every performer, from CEO to line worker, inside any organization is also part of a unique personal performance system.

- When an individual fails to produce a desired outcome in an organization, it is due to the failure of one or more components of that person’s HPS.

Figure 1: Human Performance System

The Components of the HPS

The components of any HPS, as shown in Figure 1, are as follows:The performer (1) is expected to produce some set of outputs (2). For each output there is a set of inputs (3). For every output produced (as well as for the action it took to make the output), there is a resulting set of consequences (4) – something that happens to the performer, which in turn is interpreted by the performer as either positive or negative. This interpretation is the key to understanding the performer’s future behavior, because the HPS is governed by the behavioral law that people’s behavior is affected by consequences, meaning they are likely to repeat behaviors that bring them positive consequences and also likely to avoid behaviors whose payoff is negative. The final element of the HPS is feedback (5) to the performer about the output.

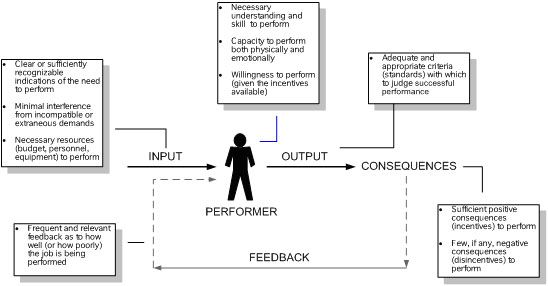

This template of human performance can be used to diagnose any performance problem, and perhaps even more important, it can be used to design better jobs. In Figure 2 is the ideal HPS, with descriptions of each component in its ideal state.

In its usage over past years, some patterns of performance have become apparent. For example, 90% of the time, performance deficiencies that might appear to be caused by a human performer, or a class of performers all doing a given job, are actually the result of other things being wrong in their HPS:

- Missing materials

- No clear direction or expected output

- Interference while trying to do their work

- Lack of any meaningful feedback

- Strong negative consequences for trying to do the job

- No positive consequences for succeeding

- Broken, unavailable, obsolete equipment

- Lack of training or other preparation

It is sometimes stunning to find out the circumstances in which average performers keep on grinding away in their duties in spite of a dreadful lack of support. HPS analysis can help bring this kind of situation dramatically to light.

Figure 2: The Ideal HPS

The Performers of the 21st Century

In many of today’s organizations, technology has become so pervasive that it functions as a frequent enabler of human performance as well as, in many cases, functioning as a performer itself. Can the HPS concept be useful here as well?

Absolutely. Technology can fail to support a process or its human performance because the circumstances in which it exists don’t support its effective utilization. Let’s call it the Technology Performance System (TPS). It can suffer from missing or poor inputs (bad data, bad data entry); unclear goals or outputs (meaning the technology may be designed to produce outputs different what is actually desired); a bad surrounding performance environment (interface problems, software issues).

Even consequences play a role in the effective performance of a TPS, in that a system, database or application can be misused or abused so that it does not do the job it was designed to do. Witness the jerry-rigging of legacy systems to perform tasks they were not originally made for, eventually leading to a crash-and-burn. Even machines don’t necessarily just suffer silently.

For process designers, improvers, managers, the HPS and TPS are essential conceptual tools for their arsenal.