If the purpose of Government is to serve the needs of the public, as many agree, the main objective of Governance is to ensure that public needs are efficiently, effectively and impartially served.

Governance mechanisms can help to achieve that objective by providing well-defined processes and structures for all aspects of procuring, deploying, and managing the use of government resources. A recent study by the World Bank found a strong relationship between good Governance and good Government performance. Other studies have revealed similar findings[1]. The purpose of this article is to underscore the need for investing adequate resources in (and leadership of) an agency’s Governance processes.

Having worked with more than a dozen federal agencies over the past 25 years, my experience suggests that their Governance, in actual practice, seldom functions as a set of highly participatory processes that lead to higher levels of performance accountability.

In many instances, enterprise governance helped to expose the reality that government agencies – instead of operating as unitary, efficiency-seeking structures – can be comprised of diverse units with (sometimes) competing interests. This conflict is not necessarily abnormal but has, for one reason or another over many years, apparently crept into the make-up, or “organizational culture”, of many agencies. As for stakeholders (i.e., those who have a vested interest in the effective functioning of the enterprise), they frequently make up the membership of multiple, often diverse groups, each of which is trying to realize benefit from improvements in organizational performance.

Indeed, stakeholders are free to pursue different aims, so long as those aspirations remain consistent with enterprise-level goals and objectives, and to seek different benefits for themselves. Employees, for example, justifiably want job security, while customers rightfully demand high-quality services and/or the timely delivery of government benefits. Taxpayers, on the other hand, expect federal, state, and local leaders to be good stewards of the public funds (and other resources) entrusted to their department, agency, bureau, or other unit of government. Whether each individual stakeholder sees it or not, these differing and potentially competitive interests do have the effect of influencing the direction of government agencies over time – and no community of interest has a better right to be heeded than any other group.

Start With an Enterprise Governance Framework

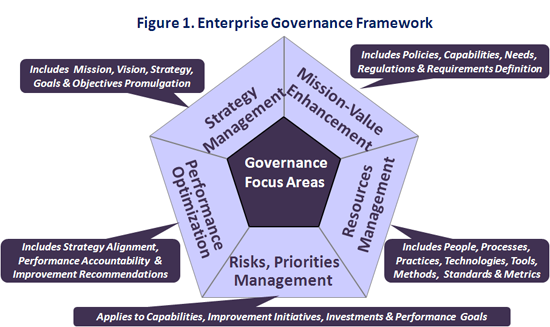

An Enterprise Governance Framework[2] is provided in Figure 1 to illustrate the dynamic nature and coverage of needed governance processes at the enterprise level of most government agencies. The following key focus areas are highlighted in this framework: Strategy Management, Mission-Value Enhancement, Resources Management, Risks and Priorities Management, and Performance Optimization.

Though the callouts in Figure 1 indicate important extensions of each of the identified focus areas, it may be useful, to drill down on at least one of the Governance areas, e.g., the Mission-Value Enhancement Focus Area:

- a. Policies, Regulations, and (Needed) Statutory Changes: This means that policies and regulations need to be governed in a manner that ensures their continued relevancy, consistency, and applicability to the ongoing mission of the enterprise. Believe it or not, this often turns out to be a rich source of issues that can have the effect of impeding performance, in many government organizations. Laws, too, can sometimes constrain an agency’s operational effectiveness and may therefore need to be changed (i.e., based on recommendations emanating from a sound Governance process).

- b. Mission Capability Needs and Business Requirements: As government missions evolve over time, often as a result of legislative changes, Governance mechanisms can be an efficient means of clarifying any impact of those changes on the strategic goals and objectives of an affected agency – which can also lead to (Governance-informed) adjustments being made to current and future investment priorities and funding profiles.

Looking further, at the Resources Management focus area of the Enterprise Governance Framework, it becomes apparent that the provisioning of any mission-enabling resource (or combination of resources, sometimes called “services”) – whether involving people, processes, technology, methods, tools, and/or standards, etc. – needs to be closely controlled by highly-participative governance mechanisms, particularly in a budget-constrained fiscal environment.

If this Enterprise Governance Framework were to be further examined, down to a third level of decomposition, one would have to acknowledge the need to govern a whole host of other (equally-important, at least to their owners) domains such as: stakeholder profiles and attributes, business logic and business rules, data models, security and privacy controls, technology standards, user licensing agreements, service-level agreements, and identity attributes (for access management and control purposes) – to name just a few.

Use Governance to Facilitate Public Accountability

Given the enormous variety of “things” to be governed in virtually any government agency, it is increasingly important for each Community-of-Practice’s key stakeholders to actively participate in relevant Enterprise Governance processes – especially in a budget-constrained fiscal environment where the adjudication of competing claims for scarce resources amounts to a zero-sum contest.

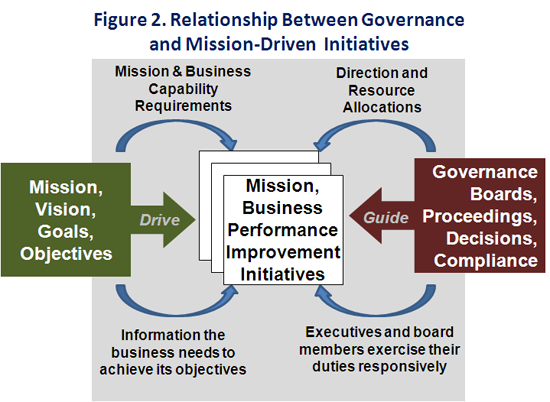

What might be called a cause-and-effect relationship, between an agency’s governance mechanisms and its mission-accomplishment capabilities, is illustrated in Figure 2.

In contrast to many enterprises operating in the private sector, where a strong leader’s vision often spawns the definition of a distinct mission statement, most government agencies have their missions essentially defined by the legislation that created (and sustains) them. Because of this, Government leaders are expected to create, and refresh over time, a compelling vision that effectively inspires their workforce (i.e., the leaders, managers, and other workers either employed or contracted by a given agency) to, collectively, accomplish the legislatively-chartered mission of their government entity. Each agency’s vision is then expected to be realized through the execution of one or more strategies, – supported by specific goals, objectives, and corresponding performance objectives –, which, taken together, comprise a “game plan” that is supposed to guide any number of initiatives designed to enable accomplishment of an agency’s mission over time.

It is important for all stakeholders of a government agency to recognize that the basic relationship that links the underpinning legislative charter, constituting the rasion d’etre of their organization to its mission performance, has the effect of creating a duty of public accountability for all individuals commissioned to lead that agency. As indicated in Figure 2 above, Governance mechanisms can prove to be essential tools for guiding continuous improvements to organizational performance, while also providing evidence that can be used to facilitate ongoing public accountability on the part of government leaders.

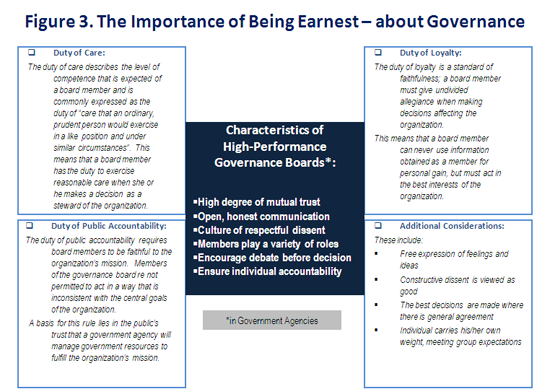

Figure 3 provides a summary of the more consequential duties of stakeholders charged with the responsibility of acting as stewards more often than not, representing their respective domain’s specialized body of knowledge, interests and equities, in Governance proceedings[3].

In Conclusion: Strategies for Success in Improving Enterprise Governance

Some of the more significant challenges to implementing Enterprise Governance processes in Government agencies – i.e., those in greater need of immediate alleviation –, include those listed below (with their respective, remedial actions):

- Direction Setting: Within any business or other knowledge domain, government stakeholders nearly always represent a diverse mix of needs and special interests, many of which are promoted with widely differing (sometimes parochial) views and objectives. This means that government leaders need to be able to distill those conflicting perspectives into a common set of strategic objectives that best serve the greater interests of the larger enterprise, while at the same time allowing as much local autonomy as practicable.

- Maintain Control: Ineffective controls may actually be the leading cause of Governance breakdowns in many government agencies. This suggests that more rigorous processes and mechanisms are needed to ensure that outcomes of Governance decisions and actions are better aligned with an agency’s strategic goals and objectives. It also means that a clear relationship must always be maintained between Governance activities and Governance outcomes.

- Manage Risks: Unforeseen risks are often frequently cited as a major contributor to the “failure” of many performance improvement initiatives undertaken by the government. This contrasts with a public expectation (as often reported by the press) that agencies need to do a much better job at identifying and managing the risks that are so frequently characterized (after-the-fact) as “unforeseen.”

- Improve Integrity: Perhaps because Government is entrusted with public funds and other resources, legislatively chartered to serve as public stewards of those resources, the need for honesty, integrity, propriety, and vigilant objectivity on the part of government officials must be continuously improved, and exemplified by greater levels of individual professionalism, higher personal standards, and the use of a rigorous framework that both encourages and rewards effective and responsive Governance.

- Share Information: Greater openness and transparency are increasingly expected by the public from government leaders. The ever growing use of the Internet and other social media has steadily stimulated the public’s thirst for more and more information. Providing ways and means for that thirst to be rapidly quenched will help to build and maintain public confidence and trust in government operations. Complete transparency for critical activities and decisions, including budget preparation and execution, must be made available to stakeholders, whenever possible.

- Monitor Results: Since public accountability is measured in terms of outcomes and perceived constituent value – and not on resource expenditures –, Governance outcomes, as well as organizational performance, must be kept high on the list of an agency’s measures of success. All performance results must also be measured relative to the agency’s own strategic goals and objectives.

[1] “What is Demand for Good Governance (DFFG)?” The aim of the DFGG Community of Practice is to increase collaboration and knowledge-sharing on DFGG activities. The Group includes members with diverse expertise and geographic focus, from World Bank staff to members from academia, civil society and other organizations.

[2] Adapted from a similar framework promoted by ISACA’s IT Governance Institute, which is primarily applicable to the governance of information technology initiatives.

[3] Adapted from “Distinguishing Governance from Management,” by Barry Bader