For years, I’ve been telling my federal customers that an IT Strategy is often not very helpful, and that all of an agency’s resources (whether people, processes, technologies, services, or facilities) should be collectively aligned and applied to enable a single enterprise strategy that is driven by mission and business needs – in short, an Enterprise Business Strategy. “Instead of an IT Strategy,”1

I would go on to say, “What an agency needs is an IT Roadmap.” Despite that advice, which did go against the grain of prevailing government practices, nearly every CIO would persist in his or her efforts to promulgate an IT Strategy – as an emblem or accoutrement of the office they held, it often seemed.

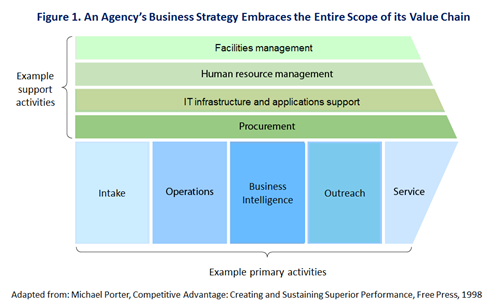

Invariably, however, the IT Strategy “owned” by the CIO would be (or would soon become) either misaligned with the Business Strategy it needed to enable, or in worst cases, be maintained separately from the business strategy. This lack-of-alignment with enterprise business strategy, though sometimes caused by an unanticipated change to business strategy and always complicated by a lengthy planning cycle, represents the greatest risk to those who maintain a standalone IT Strategy. Indeed, any other strategy promoted by a service-oriented business unit – such as Human Resources, Acquisition and Procurement, or Facilities Management, etc. – runs the same risk of drifting into a state of poor alignment with Business Strategy, for similar reasons. With both tiered and horizontal strategies competing for attention in the value chain of a government enterprise, made of primary and supporting units of business activities (as depicted in Figure 1), the risks of experiencing the adverse impacts of misaligned strategies are perhaps too great to effectively mitigate in a world of continuing budget constraints and greater performance accountability.

The predominant business value chain depicted in Figure 1 directly applies to some departments of government, such as the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), which is primarily charged with carrying out federal law enforcement activities – i.e., everything from investigations (by the FBI, DEA, ATF, etc.), to criminal prosecutions (by the Criminal Division and U.S. Attorneys, etc.) and civil litigation (by the Civil Division and the Antitrust Division, etc.), to adjudication enforcement (by the U.S. Marshals Service, the Executive Office for U.S. Trustees, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons, etc.). Clearly, most of DOJ’s “business” activities have to do with some component of the end-to-end, federal-law enforcement value chain.

For enterprise strategic planning purposes, it is important that the term “enterprise” not be used as a mere synonym for “organization,” but rather defined as “an organization formed for the undertaking of a clearly defined mission and scope – especially one of considerable complication and risk.” |

Other departments of the federal government, such as the Department of Commerce, are not structured to offer a single “business” value chain that delivers the bulk of their public services. For example, the Department of Commerce is comprised of a dozen agencies with a wide variety of “business” missions – ranging from weather forecasting, to census taking, to standards setting, to patent and trademark protection, and more –, most of which have little (if anything) to do with one another. As a result, the Department of Commerce is somewhat comparable to a holding company in the private sector – i.e., an organization made up of many distinct subsidiaries, each with its own mission to accomplish. In organizations like the Commerce Department, it is important that enterprise mission, vision, and strategy – including “enterprise business strategy” – be defined at the agency level, e.g., for the Census Bureau, for NOAA, for Patents and Trademarks, etc. (though organizations like the Commerce Department and the Interior Department do promote abstract visions at the department level, like “making American businesses more innovative at home and more competitive abroad” and “protecting America’s great outdoors and powering our future”).

For enterprise strategic planning purposes, it is important that the term “enterprise” not be used as a mere synonym for “organization,” but defined as “an organization formed for the purpose of accomplishing a clearly defined mission and scope – especially one of considerable complication and risk.” In many instances within government, an enterprise extends beyond the borders of a single agency, department, or even a nation. Interpol, the International Criminal Police Organization, is one example of such an enterprise; the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is another. The point is that the concept of an enterprise is at once scalable, divisible, and capable of working in partnership with other enterprises – like, for example, the Department of Defense (DoD), which can operate as an enterprise in alliance with the military forces of other countries to form a larger enterprise (like NATO) – while at same time the DoD’s own military forces can be deployed, for operational purposes, to collaborate with its Allies to support sub-enterprises (e.g., one that is largely focused on air operations, another on naval and marine operations, and yet another on land operations).

Each of the enterprises identified above needs to be grounded in, and guided by, its own “enterprise business strategy.” Yes, some of those strategies will have overlapping aspects and some will be dependent on the strategies of other enterprises, and all of those coincidental strategic aspects need to be iteratively de-conflicted over time. What each enterprise doesn’t need to contend with, however, is the self-inflicted need to ensure that other, internal support functions (e.g., HR, Facilities, IT, etc.) must keep their subordinate strategies always in synchronization with an evolving Enterprise Business Strategy. Instead, they need to use Roadmaps as agile mechanisms for assuring their continuous alignment with the Enterprise Business Strategy.

How to Help Business Leaders Craft a Useable Enterprise Business Strategy

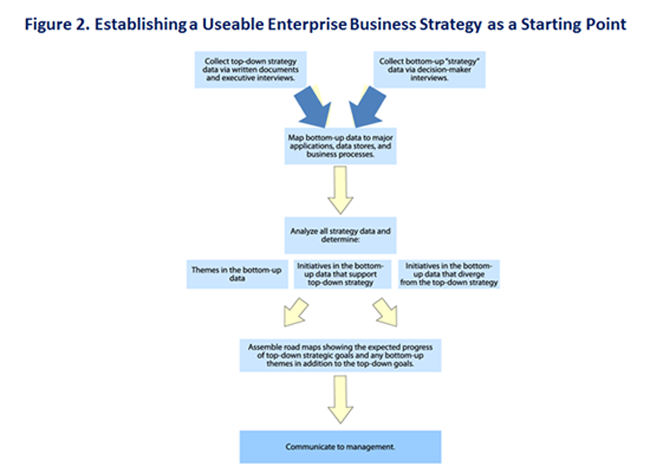

As noted above, some of my federal CIO customers have been countering my position that IT Roadmaps are needed instead of IT Strategies, by suggesting that their organization’s Enterprise Business Strategy was inadequate and/or not executable, and that they couldn’t afford to wait until those deficiencies were resolved. My response – to the effect that they should work with relevant business leaders to quickly construct a Business Strategy (and not start without one) – might have begged the question of how to do that on short order. Figure 2, below, illustrates how I answered that question from time-to-time. I’m hoping it might help others who may be facing that same quandary today.

Incidentally, it is not at all unusual to learn that a government organization’s future, i.e., beyond the end of the current budget cycle, is a lot less well-thought-out than most people would expect. When in such a situation, it shouldn’t be assumed that you can’t get to an Enterprise Business Strategy from such a dismal starting point. After all, most IT investments run the grave risk of producing poor returns without the benefit of being informed by a viable and actionable (not to mention, “defensible”) business strategy.

As indicated in Figure 2, one should launch an aggressive initiative to gather and analyze the information that is needed by following these relatively uncomplicated steps:

- Collect Available Information and Data – Gather whatever plans can be found, even if they are somewhat dated. Collect the last couple of years’ worth of available project data, zooming in on major projects (their descriptions, justifications, and whether they were approved). Find documentation on the business strategies of the enterprise and other, similar government agencies as well, using public information like newspaper articles, web-sites, and any available case studies.

- Meet with Key Business Leaders (to Capture their Most Important Goals) – Interview business leaders, including business owners and senior executives in functional areas such as human resources and procurement. These leaders will have different priorities, of course, and part of this exercise will lead to discoveries of commonalities across the group. Include senior level managers who have more operational concerns. Also include recognized thought leaders and decision-makers who are not necessarily in management positions. Don’t expect straightforward responses to your requests for views of the future — you will have to elicit this type of information them with careful questioning.

- Adjust Interview Approach to Each Audience – For staff level interviewees, use an approach that relies on short sessions and simple questions that exposes their view of the future, while providing assurances that all responses will remain anonymous. Depending on the size of your organization, this may require careful scheduling; otherwise, the scale may be discouraging. You should also balance workload among your available data-gathering staff, so that each “researcher” covers 20-to-30 interviews over 60-to-90 day period.

- Organize Findings Based on Implications of Current and Emerging Strategies – Collect your findings in at least two groups: the stated top-down strategy derived from executives and strategy documents, and the strategy that emerges from the operational view. Analyze project approval and priority data for their relevance to overall enterprise priorities. Use what you know about the current state architecture to look at interdependencies, and follow out the implications of current and near-term activities. Summarize your findings in a series of road maps that show business unit progress and enterprise-level capabilities as they will evolve given the forces that you observed and analyzed.

- Reconsider Findings with Business Leaders – Based on your findings, explain to senior executives where the enterprise appears to be headed. It could be that the activity aligns pretty well with current strategy, or the results may indicate that enterprise activity appears to be diverging from where the top-down strategy suggests it should be headed. Ask the executives for an accurate vision of the future state, and seek help for developing the tactics needed to realize that vision. Follow up on any discrepancies, and obtain executive commitment for their resolution.

- Repeat the Process on an Annual Basis – While it may not be practical to repeat this process more often than once a year, a semi-annual refresh is recommended. For the intermediate reviews, one can use collected project metrics, records of governance process proceedings, and data collected for balanced scorecard reporting purposes, to gauge progress and detect any drifting from approved strategy.

What is an IT Roadmap?

An IT Roadmap is a long-term plan that attempts to track specific technology services and solutions – and the sequence(s) in which they need to be planned, programmed, budgeted, executed, and evaluated – for the purpose of enabling the Enterprise Business Strategy. The use of such a roadmap serves the following purposes:

“. . . [T]he IT Roadmap should be developed to support the business vision to help avoid the fate described by Mr. Lewis Carroll, when he (allegedly) observed: “If you don’t know where you want to go, any road will get you there.” |

It helps business executives and senior IT leaders reach a consensus about the information technologies and other enabling services that will be required over time to satisfy the business needs and mission capabilities (either explicitly or implicitly) identified in the Enterprise Business Strategy

- It provides a convenient mechanism for facilitating the forecasting of emerging technology and service needs (both in terms of new ones and in terms of those that need to be phased out-of-service)

- It provides an evolving framework to help plan, program, budget and coordinate the insertion of new technologies and other service changes over multiple years

Too many people tend to view the IT Roadmap as an end unto itself, and not as a means to the end. The IT Roadmap should be developed in response to the Enterprise Business Strategy as the embodiment of an action plan that secures the business vision and not the other way around. Since IT has become, over the past six or seven decades, a critical enabler of business strategy, the IT Roadmap should be developed to actualize the business vision, and to help avoid the condition described by Mr. Lewis Carroll, when he (allegedly) observed: “If you don’t know where you want to go, any road will get you there2.”

1 A few of my federal CIO customers countered with the argument that their organization’s Enterprise Business Strategy was inadequate and/or not executable, and that they couldn’t afford to wait until those deficiencies were resolved. In those instances, I advised them not to prepare an IT Strategy in lieu of a Business Strategy, but to join forces with business leaders to help them craft a useable Enterprise Business Strategy.

2 Though this line is often attributed to Lewis Carroll, it is not in the Alice in Wonderland books. The actual exchange – which also applies to the situation described in this article – is as follows:

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where–” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“–so long as I get SOMEWHERE,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.”