As is the case with many of us in the Business Architecture forums, my career is firmly rooted in computer science and information technology. The first few years of my professional life found me devising algorithms, designing databases and writing code for various organizations around the Washington, D.C. beltway. It was a pleasant and satisfying endeavor, well suited to my quiet disposition. Despite the unavoidable meetings with end users – which meetings never failed to throw a monkey-wrench into my carefully crafted programs – my projects tended to unfold without major heartaches while I dug deeper into James Martin’s Information Engineering, Barry Boehm’s Spiral Model for Software Development, and Barbara von Halle’s writings on data architecture and business rules. The success of my early-career projects led my higher-ups to infer some sort of causality between my presence on those projects and their fortuitous trajectory, and to therefore tag me as management material.

The wonderful times of the ‘90s, when everything was growth, growth, growth, allowed me to mature, in parallel, both as an architect as well as a projects and people manager, each side of my career balancing and reinforcing the other. After the dot-com bubble burst and the Chief Information Officer Council’s “A Practical Guide to Federal Enterprise Architecture” was published, I embraced the principles and the framework offered by the nascent Enterprise Architecture discipline not just because they sought to systematize the IT layer, but because they were applicable to the enterprise as a whole. The more recent advent of Business Architecture as an outgrowth of Enterprise Architecture served to solidify in my mind the notion that every aspect of the social organism which is the enterprise can be blueprinted and articulated in a structured way, and that doing so increases the predictability of success – however success is defined for each component fi the enterprise.

***

Fast forward to today. In my current role as a business executive, my focus is on furthering my company’s mission in ways that are significant to my clients, meaningful to my team, and accretive to the company’s assets and capabilities. To understand my clients, I first need to learn their business – their vision and strategy, their value chain, their business processes, so I can then locate the gaps and areas of weakness in their business and enterprise architecture. Where do the problems lie? At the boundary between processes? In the movement of data through the enterprise? In the lack of automation or, quite the opposite, in the proliferation of siloed systems? Or, perhaps, is it the human factor – lack of expertise, obsolete skillsets, unhealthy organizational culture, suboptimal organizational structures – that is the crux of the problem?

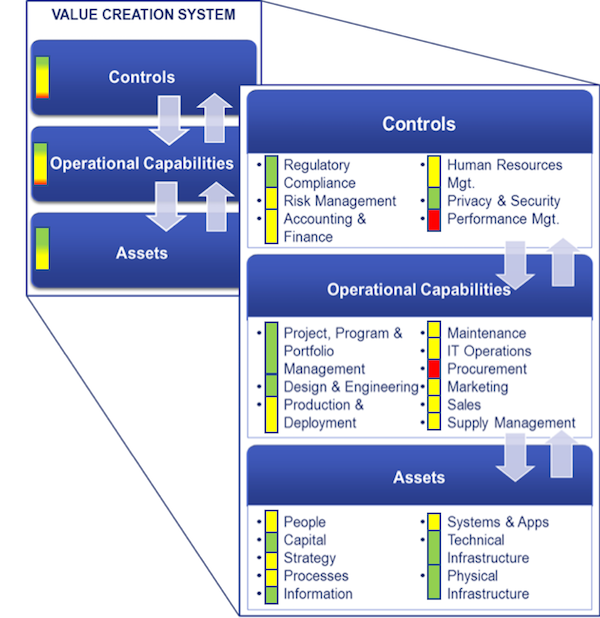

In previous articles I described the business enterprise as a Value-Creation System[i] composed of assets, controls and operational capabilities, all spurred into action by environmental stimuli, adaptive decision-making activities, and internal disruptors[ii]. The way I assess my client’s “business health” is to mentally (or on paper) break down their organization into the individual components of the value-creation system, as shown in Figure 1, and assign traffic-light style indicators to each component. This quick exercise gives me a bird’s eye view of the client organization as well as an early warning of areas where my clients may be encountering difficulties or developmental delays, and it shapes the nature of my message and approach in client interactions.

I apply the same technique when assessing my own company’s assets and capabilities, whether for the purpose of strategic planning or to fill in gaps in our capabilities. For instance, not so long ago I was working for an employer that was undergoing aggressive growth, but whose ability to attract and hire a large number of new staff in a short amount of time was undercut by its still nascent talent acquisition and talent absorption processes. Much like in the model shown in Figure 1, the company’s Procurement operational capability was close to a “red” status – i.e., adequate for one-off hirings but unprepared for large intakes of new hires. Adding to the challenge, the company’s Human Resources Management controls (which reflect the company’s ability to regulate staff management in compliance with established policies and principles) were also in their early stages of maturation, with HR policies still being defined and socialized with the staff, and the application of policies left to the preferences of individual managers – so, close to a “yellow” status.

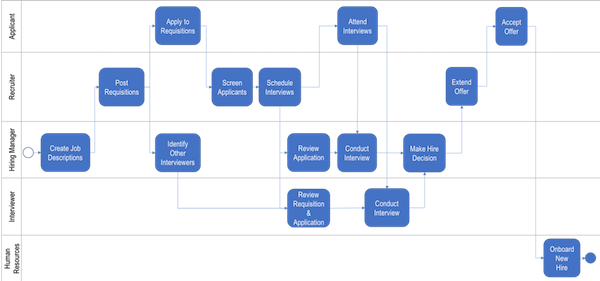

Faced with the prospect of stumbling at the first step into a new contract due to our unpreparedness to adequately staff up, I put pen on paper and, together with members of our HR group, defined a clear, repeatable series of steps for intaking job applicants.

Figure 2: A high-level view of the staffing process

The process in Figure 2 is a simplified, high-level illustration of the actual process we developed to support the screening and hiring of a significant number of new resources. Unlike the “happy path” variant of the process (shown above), the actual process we defined to handle the situation at hand took a larger number of considerations into account, such as:

- Did the applicant submit the application online, or in person at our job fair?

- Was the candidate already familiar with our company, or would we have to provide a brief overview of the company prior to scheduling interviews?

- Did the candidate apply to only one position, or to multiple positions?

- Did the candidate fail the initial screening with the recruiter? If so, was the candidate still a potential match for other openings?

- Was the candidate a direct applicant, or was he/she submitted to us by one of our subcontractors?

- Were the candidate’s compensation and benefits expectations in line with our budget? Who would need to be involved in the negotiation process?

- Did the candidate have the required security clearance?

Each one of these factors led to new branches in the process model, so having the scenarios laid out and documented allowed us to traverse all the possible scenarios on paper before executing them in real life, and laid the foundation for future automation of parts of the process flow.

***

These are only a couple of examples but they are indicative of a pattern, which is that even though most days my focus is sustaining and growing the business, the repertoire of methods and tools I instinctively turn to draws heavily on Business and Enterprise Architecture practices. The challenge that myself and many other business managers face is one of planning horizon: we focus on meeting our company’s operational goals for the current quarter, or the current half-year, or the current year. We are mired in tactical work. In a hard-to-predict economy, we manage increasingly complex, matrixed organizations, navigating complicated networks of interests and counter-interests, while delivering value to clients whose own organizations are similarly complex. For us, the definition of the value of Business Architecture proposed by IASA[iii] rings particularly true.

[i]Lovin, S. “The Value Creation System”. The Value Creation Blog. January 2, 2017.

[ii]Lovin, S. “Disruption, Innovation and the Art of Business Architecture”. BAInstitute.org. 2017.

[iii] IASA Global, On the Value of Business Architecture.