Risk assessments have become more common recently, and for good reason. We read headlines daily about data breaches, high-dollar investments gone wrong, and companies that took a market risk that didn’t pay off.

Risk increases as a result of change, whether internally or externally triggered. Examples of internally driven change include executing a new project, launching a new product, or changing a process. Regulatory requirements, market changes, competitive challenges, and new security threats change the risk profile even when a company is conducting business as usual. Enterprises are never done with assessing risks; there is no such thing as “steady state” when it comes to risks.

Risks, or threats, have been described as unrealized constraints; that is, something that may occur but is not yet proven to be true. Risks may be wholly or partially within our control. They may be something we can prevent, something we can recover from, or something we can live with should they occur.

Here I provide a simple framework to identify the risks, rank them in a priority order, and determine what action, if any, must be taken for each.

External changes are often industry dependent. Consider these, which are largely outside a company’s control:

- Legal or liability claims

- Increased competition

- Regulatory changes and requirements

- Economic downturns that create a lack of demand

- Supply or materials constraints

- A critical mass of knowledge workers reaching retirement age

- Lack of qualified job applicants

- Data security breaches

Internal Changes can include process changes, reorganizations, and projects. Each carries unique risks, but many are common to all three:

- Lack of personnel, either not enough or those without the needed skills

- Changes in scope

- Not meeting success criteria

- Not delivering the project on time

- Not staying within the project budget

- Insufficient executive sponsorship

- Inadequate tools

- Incomplete/badly understood requirements

- Undocumented or undiscovered processes/workarounds

- Poor process design

- Ineffective change management strategy

- Lack of stakeholder buy-in

- Not all stakeholders identified

- Inadequate training for new processes

- Employees lack skills needed for new processes

- Employee resistance to change

- Employee morale decreases

- Unplanned impact on upstream/downstream processes

Risk Assessment Framework

Five basic questions are common to all risk assessments:

- What is the risk?

- How likely is the risk?

- What is the impact of the risk being realized?

- Can we prevent the risk, and if so at what cost?

- What happens if we do nothing to address this identified risk?

We can enter the answers to these questions in a simple matrix that will include calculations to rate and prioritize each risk, and allow you to balance the cost of mitigation against its impact and the likelihood of its occurring.

Initially, list these elements for each risk identified:

- A textual description of the risk

- A textual description of the impact of the risk, should it occur

- An estimate of the cost of the impact, expressed in a simple 1 (low), 2 (medium), 3 (high) scale

- An indication of the likelihood of the risk occurring, expressed in the same scale

Now multiply the number for the likelihood of the risk being realized against by the number representing the impact. This results in a ranked list of risks, the first part of your matrix.

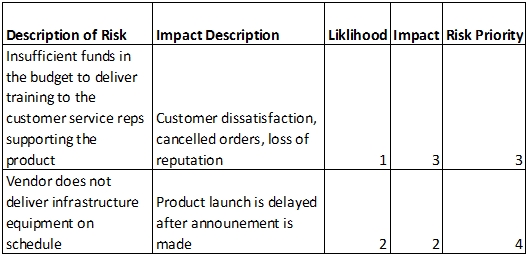

As an example, in Table 1 the impact of customer dissatisfaction and loss of orders for a new product may seem like a very important risk to mitigate, but it has been ranked as unlikely to occur. Therefore, the possibility of the vendor delivering the needed equipment late will be prioritized over the training budget when considering mitigation strategies.

Table 1

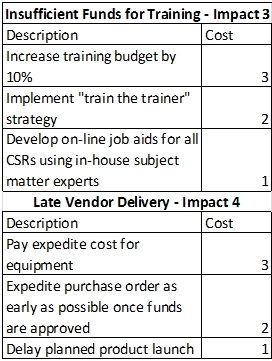

Once the risks have been ranked and ordered, consider what it will take to mitigate each risk. Develop a list of options that includes what you might do to prevent it from occurring, or to recover if the risk occurs. Estimate the cost for each option, again using a 1-2-3 ranking. Table 2 provides an example of three options developed for the risks listed in Table 1, and the cost for each.

Table 2

Giving absolute scores to these factors allows you to balance the cost of your mitigation strategy against the priority of each risk. In some cases, where probability and impact both are low, the choice to do nothing is a valid one. Each mitigation strategy needs to be funded as a contingency in the budget, and returned to the funding body if the risks are not realized.

In some cases, where risk impact and probability are both low, you may choose to do nothing. This is a valid choice, but once a risk is identified the decision to mitigate or accept the risk belongs to the project’s sponsor. It is critical to discuss and document all such decisions, and it’s always wise to require formal approval or signoff by the sponsor of the change.

The scales presented can be expanded to provide more granularity if there are many competing risks. You may also choose to employ a High/Medium/Low scheme and skip the math, and simply eyeball the impacts and costs.

Make no mistake, risk assessments are not simple. Methods such as the one described above can aid the project owner in quantifying risk factors, but there is skill, art, and experience required both in identifying risks and in deciding what to do about them. Bring in experts from across all functions to brainstorm the topic. Spend this time and effort as you are planning any change, at the first indication of a significant environmental change, and on anything that hasn’t had a risk assessment for a period of time. You can’t afford not to.