In one of my earlier articles on Disruption, Innovation and the Art of Business Architecture, I made the case that the concept of entropy is highly applicable in explaining the evolution of business organizations.

Generally speaking, entropy is the measure of disorder in a closed system, and it is a concept borrowed from thermodynamics – the branch of physics that deals with the relationship between heat, work, temperature, and energy in a system.

While a business organization is an open system rather than a closed one – as it exchanges information (energy) and physical resources (matter) with its environment – the concept of entropy still applies, albeit in a modified form, as a measurement of the system’s probability to change. The higher the level of entropy, the higher the probability that the business organization will undergo a significant change. The change can be positive, leading to so-called “emergent properties” such as innovation and self-governing behaviors, or can be negative – leading to devolution and implosion.

Economists and management cyberneticists such as Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Stafford Beer have found that in turbulent business environments with high entropy levels (i.e., high levels of chaos and uncertainty), it is effectively impossible to predict whether the organization is about to change for the better or for the worse . Moreover, if the change is for the worse, that change is irreversible and is bound to result in the collapse of the organization. The good news for a business organization is that in an open system entropy can be controlled, to some degree, by adjusting the system’s exchanges with its environment.

A Bit of History

What scientists have discovered by studying thermodynamics and complex systems, good leaders have figured out intuitively, through trial-and-error and by learning from past successes and failures.

Throughout history, those individuals who have sensed the importance of taming social and organizational chaos by integrating the existing knowledge and tools and by creating repeatable processes are the ones who have emerged as leaders within their group, community or organization. One might even say that, from this perspective, the entire human evolution has been nothing but a relentless march towards greater integration and process optimization.

Five thousand years ago, ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia built large irrigation systems to control the flow of water for agricultural purposes. More than two thousand years ago, the Romans streamlined their transportation and ‘supply chain management processes’ by building a complex system of roads between Rome and its provinces. During the Medieval period, the increased demand for precious metals led to a transformation in the business model for the mining industry, where mining operations changed from an artisanal, family-based model to state-run, large-scale mining. The change in the business model for ore mining was aided by integration and automation improvements, whereby new technologies such waterwheel-based pumps, bucket chains and treadmill devices supplemented the traditional manual labor .

The pace of integration and process optimization accelerated during the past two hundred years with the transition to new manufacturing processes (the First Industrial Revolution), rapid industrialization and mass-production (the Second Industrial Revolution), and ubiquitous digitization (the Third Industrial Revolution, still ongoing).

Moreover, the field of integration and process optimization itself became the subject of much research and formalization starting in the early 20th century, which resulted in a string of influential theories ranging from Statistical Quality Control (Walter Shewhart), Total Quality Management (W. Edwards Deming), Lean Manufacturing (The Toyota Way), Six Sigma (Bill Smith of Motorola) to today’s various Agile frameworks.

Figure 1: Illustration of water-powered process automation mechanisms in the mining industry, mid-16th century. From De Re Metallica, by Georgius Agricola, 1556.

Nowadays, according to Professor Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum , we find ourselves at the dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution – a phase of exponential transformation across value chains, propelled by the spread of artificial-intelligence tools such as machine learning, natural language tools, and cognitive agents. “The Fourth Industrial Revolution is disrupting almost every industry in every country and creating massive change in a non-linear way at unprecedented speed”, Professor Schwab states in his seminal book, The Fourth Industrial Revolution. He is not alone in his views, as similar sentiments are echoed by thought leaders and industry titans such as Peter Diamandis, Founder & Executive Chairman of the XPRIZE Foundation; Ray Kurzweil, one of the world’s leading inventors and futurists; Sergey Brin, co-founder of Google; Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX and Tesla; and by many others.

Research done by think tanks such as the McKinsey Global Institute confirms this global trend and estimates that, across industries, more than 30 percent of the tasks that make up 60 percent of today’s jobs have the potential for being automated . The high-tech and telecom industries are currently leading the way on automation, according to a survey performed in 2018 by McKinsey, but huge opportunities for automation also exist in finance, insurance, Human Resources (HR) management – industries where workers spend more than half their time collecting and processing data.

Where does Robotic Process Automation (RPA) fit in all this?

RPA has its roots in the 3rd Industrial Revolution, as on outgrowth of organizations’ quest for attaining higher efficiencies through enterprise integration. The term “globally integrated enterprise ” was coined by Sam Palmisano, former CEO of IBM, in 2006, to denote “a company that fashions its strategy, its management, and its operations in pursuit of a new goal: the integration of production and value delivery worldwide.” The “integrated enterprise” terminology and the philosophy behind it caught traction not only with multinationals but also with more modestly-sized enterprises, and propelled businesses everywhere towards striving to extract higher productivity, better quality and lower costs out of their scarce resources through enterprise integration.

RPA is one of the tools organizations have at their disposal for increasing the level of enterprise integration. It is not the only tool, and it is by no means a panacea, but used in conjunction with other frameworks and tools it can lead to substantial increases in the efficiency of a company’s operations. In fact, when RPA is paired with Artificial Intelligence technologies such as natural language processing, machine learning, predictive analytics, and computer vision, RPA applications can in fact cross over into the 4th Industrial Revolution realm, where they are able to read the context, assess it, make predictions and provide insights.

Let’s unpack these ideas by taking a closer look at what RPA is – and what it isn’t.

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) – A Brief Description

According to the UIPath, one of the top software makers in the industry, RPA is a technology that allows users to build software “robots” that emulate the actions of a human interacting with various information systems to execute a business process. The RPA robots, once launched, can manipulate applications in a way that imitates how human users interface with those applications. RPA robots can log into applications, copy data from an image or an application, paste data into another application or electronic form, extract data from browsers – and do this again and again, accurately and around the clock. Simple activities based on pre-defined decision paths may be performed entirely by a so-called “unattended RPA robot”, while more complex activities that require a human’s input or judgement call to trigger an action can be programmed into “attended RPA robots” that act as productivity aids to human users.

Just like a human employee, the RPA robot acts at the application’s Graphical User Interface (GUI) level, by using the information that is presented to it through the GUI. In the words of The Lab consulting firm, a company which specializes in improvement through standardization: “When properly configured, RPA knits together mainframe fields, cloud-based software fields, and desktop applications like Excel into a single, streamlined, standardized, and automatic process. “

Unlike a human employee, a RPA robot can perform a repetitive activity very fast, error-free, with no need for breaks, and therefore more cost-effectively. This presents significant benefits, not least of which being the fact that RPA robots can relieve the human workforce of huge amounts of routine work – for example by monitoring sites for specific types of information, sifting through reams of documentation, searching large database systems, or analyzing and replying to questions or requests from customers.

Other benefits include:

- RPA robots can easily ramp up to handle spikes in demand, with zero delays and at little additional cost.

- Since the RPA robots’ activities are automated through software, every action they take leaves behind a complete and auditable audit trail.

- RPA robots are continuously productive independently of time-zones and geographical locations. For organizations working with offshored and near-shored staffing, RPA robots may prove to be an overall more cost-effective alternative.

- Since RPA robots are programmed to handle small sets of activities, maintaining and modifying a robot is fairly easy and can be done by business users (although IT support is generally advisable).

One area ripe for using RPA to speed up execution is the insurance industry. Taking health insurance as an illustration, large health insurers such as the BlueCross BlueShield companies have, over time, created layers upon layers of processes and information systems. They struggle to operate a cornucopia of technologies, many still mainframe-based, while at the same time striving to stay in lock-step with continuously evolving legislation and regulatory requirements. Claims processing is a complex endeavor by which medical claims submitted by health care providers get compared against a roster of eligibility conditions, health insurance plans and policies, provider network contracts, cohorts of exception rules and so forth. Claims processing agents often have to switch between disparate systems and databases to gather the data they need to verify a claim, and frequently have to make calls to the originating providers to get additional clarifications.

RPA robots can alleviate much of the routine research work by logging into the appropriate systems, extracting, comparing and collating data, and only escalating to the claims processing agents’ attention those claims that cannot be resolved through pre-programmed business rules. In an article published in 2018, The Lab consultancy estimated that leveraging RPA to close “the last mile” in claims processing could lead to a 50% reduction of health insurance claims processing costs, and to an increase in claims processing speed by up to 70%.

Still, before jumping to the conclusion that RPA can solve all integration-related ills and challenges, it is important to note that the following key points:

- RPA contributes to the enterprise integration by acting at the system (and specifically at the presentation/GUI) layer;

- RPA assists with process automation, but NOT with process improvement; and,

- RPA does NOT replace system integration at the platform, technology, and data layers of the architecture stack.

The last point is particularly critical in understanding the difference between RPA and ‘traditional’ system integration. RPA is not a data exchange mechanism between systems, and it is not intended to provide long-term, large-scale system integration across all (or even most) architectural layers. What it does provide is an expedient and relatively inexpensive way to bypass big-budget system integration initiatives in favor of immediate results and ROI.

Leslie Willcocks, professor of technology, work, and globalization at the London School of Economics’ Department of Management, describes the business case for RPA as follows: “When organizations consider proof-of-concept for RPA, they look at the business case and compare it to an IT solution. Often that’s pretty unflattering for IT. In one organization we looked at, the return on investment for RPA was about 200 percent in the first year, and they could implement it within three months. The IT solution did the same thing but with a three-year payback period, and it was going to take nine months to implement. ”

For business decision-makers responsible for delivering results and showing progress quickly – the RPA option can be a winner.

Business Architecture as Critical Input for Successful RPA Implementations

This summer I decided, somewhat on the spur of the moment, to go to Los Angeles for a couple of weeks for sightseeing. The timing was right as I happened to have a lull in my schedule, and my relative in L.A. was out of town so I had his place all at my disposal.

Lo’ and behold, no sooner did I arrive in L.A. when temperatures spiked above 100 degrees Fahrenheit and the city turned into a massive oven. So, marooned inside my apartment for most of my L.A. vacation and with plenty of time on my hands, I did the next best thing possible and took the free RPA online training offered by UIPath. (Disclaimer: I have absolutely no affiliation with UIPath.)

The RPA implementation training was, first off, comprehensive, well-structured and persuasively presented. However, I couldn’t help but notice that no mention at all was made of the value offered by business architects in supporting an RPA initiative.

Let me elaborate on why this is a gap – and, to do so, let me start by describing the implementation methodology recommended by UIPath, with the note that the methodology is not tool-specific and that other vendors such as Blue Prism and WorkFusion recommend similar approaches.

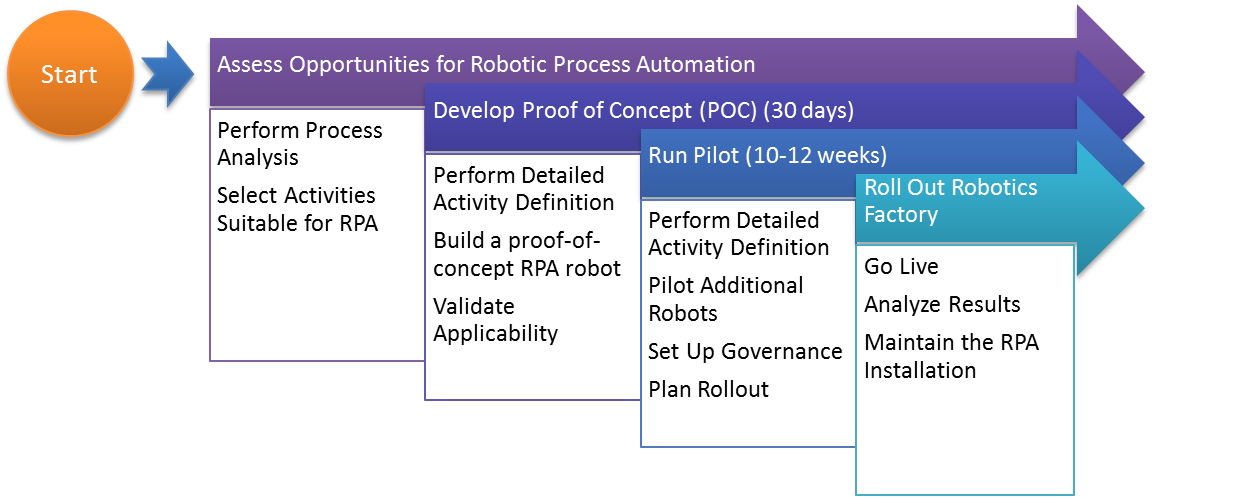

Figure 2: Typical RPA Implementation – High Level Steps

As shown in Figure 2 above, a typical RPA implementation consists of four phases:

- Selecting the most suitable activities for automation;

- Choosing a first activity to serve as a proof of concept for the RPA and developing software robots to automate the process;

- Expanding the pilot to include the remainder of the activities selected for automation while putting in place governance and maintenance mechanisms to maintain the integrity of the RPA installation; and

- Rolling out the RPA robots for use in production.

Of these phases, the initial (and arguably the most important) phase of the RPA implementation is the selection of activities best suited for RPA. To minimize re-work and keep the RPA implementation cost-effective, the methodology recommends zeroing in on activities with the following characteristics:

- Highly manual, repetitive, and performed on a frequent basis (at least daily or weekly);

- Large volumes of transactions;

- Based on clear, standardized rules;

- Mature and stable, and not slated for any changes in the short term;

- Receive input data in a standard readable electronic format;

- Have few or no exceptions requiring special handling; and,

- The savings accrued through automation are equivalent to at least 2 fulltime employees’ costs.

In summary, these criteria ensure that activities selected for automation are impactful, are not subject to near-term change, are not too trivial, and once automated, can be executed with minimal human intervention. The selection process weeds out those activities that are redundant, duplicative or ill-defined, which should be the subject of business process improvements. It also leaves out activities supported by systems about to be replaced.

By including business architects into this effort, the organization can substantially speed up the selection processes as the existing business architecture repository or knowledgebase already contains an inventory of capabilities, processes and subsumed activities, together with metadata concerning alignment with policies and/or goals, currency or obsolescence, usage, criticality (in the form of value streams), as well as data and system mappings.

During the next two phases (Proof of Concept and Pilot), the activities selected for automation are analyzed in minute detail, step by step, and then replicated into software-driven actions by using the robot-building features offered by UIPath and other similar RPA tools. For the robot to work properly, it is imperative that each and every action performed by the human operator be mirrored, precisely and in its entirety, by the RPA robot.

Here, too, engaging with the business architects in the client organization can yield precision and efficiency benefits. Whether in the form of process flow diagrams, BPMN diagrams, decision trees, business rule matrices, use case scenarios, state-based tables and/or event-based models, business architects already have the core ingredients required for an accurate process or activity definition.

Additional tools such as process mining, which entails parsing the system event logs for those activities supported by existing information systems, can augment the existing process architecture information with real-life, granular activity data.

A summary of the organization’s extant artifacts and other inputs essential for RPA implementation purposes is provided in the pdf download below. As the table shows, business architecture is not the only source of information for RPA; other valuable inputs come from adjacent disciplines – for example, business analysis and process engineering. Used in concert, these inputs reinforce each other and provide the RPA analysts with a rich source of foundational data to mine, compare and contrast, in order to arrive at the ‘final truth’ which can be programmed into an RPA robot.

Summary

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) has emerged as a critical tool in our march forward towards greater integration and process optimization. While RPA alone is not a panacea, RPA can provide high value in a short timeframe for those business functions comprised of manual, routine, and highly repetitive human activities.

Once an organization decides to invest in RPA, the implementation team does not have to start with a blank sheet of paper. Most organizations have already invested in disciplines such as business architecture, business analysis, process improvement and even process engineering. In the spirit of good business architecture practices, those responsible for the success of the RPA adoption should look for opportunities to reuse and upvalue the work that has already been done internally. Business architecture artifacts, in conjunction with business analysis documentation, process improvement outputs and process mining reports, provide a solid foundation to any RPA implementation efforts and can contribute positively to the speed, precision and success of RPA.

References:

Peon-Escalante, I., Tejeid, R., & Badillo, I. (2007). Entropy and Emergence in Organizations under a Turbulent Environment. Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the ISSS – 2007, Tokyo, Japan. Retrieved from http://journals.isss.org/index.php/proceedings51st/article/viewFile/469/255

Agricola, Georgius, (1556), Translation President Herbert Hoover, 1912, De re metallica. Retrieved from http://farlang.com/books/agricola-hoover-de-re-metallica

Schwab, K. (n.d.). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/pages/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-by-klaus-schwab

Berruti, F., Chandratre, G., & Rab, McKinsey & Company, Z. (n.d.). (2018, October). The new frontier: Agile automation at scale. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/the-new-frontier-agile-automation-at-scale

McKinsey & Company. (2018, September). The automation imperative. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/the-automation-imperative

Palmisano, Sam. (2006, March 15). “The Globally Integrated Enterprise”.

Jain, N. (2019, January 25). Top Robotic Process Automation Companies in 2019. Retrieved from https://www.whizlabs.com/blog/top-rpa-companies-2/

The Lab. (2018, August 03). RPA in healthcare – A guide in health insurance robotics (with use cases). Retrieved from https://thelabconsulting.com/health-insurance-rpa-use-case/

Id.

McKinsey&Company. (2017, March). The value of robotic process automation: An interview with Professor Leslie Willcocks. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Financial Services/Our Insights/The value of robotic process automation/The-value-of-robotic-process-automation.ashx

Ulrich , W., & Kuehn, W. (2015). Business Architecture: Setting the Record Straight. Retrieved from https://www.omg.org/news/meetings/tc/ca-15/special-events/Business_Architecture_Setting_the_Record_Straight_Ulrich-Kuehn_07-2015.pdf