I have been teaching an executive course called Designing Operating Models for four years and the tool that I consider to be most important to good operating model work is something I call a Value Chain Map. For those of you who work on processes, a Value Chain Map is a high-level process map or value stream map: the term value chain coming from the strategy literature. I prefer the term value chain because it reminds me that we are trying to link operations to strategy.

To create a Value Chain Map, you first need to identify the different “value propositions” (the products or services) that the organization offers. Ashridge Business School offers tailored courses for executives, open courses, qualifications courses, research papers and books and even weddings, using our beautiful building. An HR function might offer talent development, recruitment, remuneration and organisation development services. A factory might produce standard products and specials.

Figuring out the best way of defining the value propositions is not a trivial task. Should I think of Ashridge as offering courses, research papers and weddings, or should I think of Ashridge as offering open courses, tailored courses, qualifications courses, etc, or should I think of Ashridge as offering finance courses, marketing courses, leadership courses, etc, or should I think of Ashridge as offering 1 day courses, 2 day courses, 3 day courses, etc? The answer should come from the strategy: how does the strategy chunk up Ashridge’s different services into groups/segments/offers?

Armed with a way of defining the value propositions, lay out the high-level process steps needed to create each value proposition. So for “open courses” the steps would be

- Market to companies

- Design courses for prospective clients

- Agree terms and contract with client

- Deliver course

- Invoice and collect money

- Follow up with client

It is helpful to keep the number of different value propositions and the number of steps in each high-level process to less than seven (aggregate if needed). The reason is that you need to be able to hold the whole Value Chain Map in your head at one time; and a matrix of 36 is about the maximum you can cope with. It is always possible to go into more detail later, as needed.

When you have done high-level process steps for each value proposition, you can then create a Value Chain Map. Draw the process steps as chains along the horizontal, one above the other. Then arrange individual steps into columns of like capability. So that the “design” activity in each chain sits in one column and the “deliver” activity sits in another column, etc. (see exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1

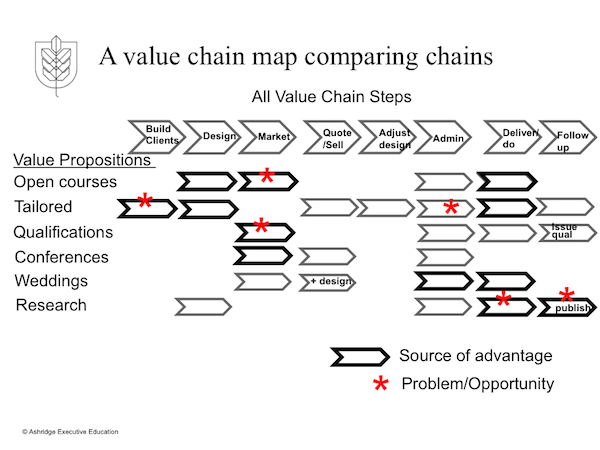

Once created, additional information can be added to the value chain map (see exhibit 2).

- Identify which chevrons in each chain are critical success factors for delivering the value proposition: which are potential sources of excellence or advantage.

- Identify in which chevrons the organization currently has difficulties or is underperforming. For these problem chevrons, it is often helpful to go to the next level of detail: breaking the chevron down into five or so more detailed chevrons and considering where the problem is at the next level of detail.

- Identify how the organization’s costs or headcount divides amongst the chevrons.

Exhibit 2

However, the main benefit of the Value Chain Map is that it provides a visual background for considering organization structure. The people doing the work in each chevron of the map could report along the value chain to someone responsible for ensuring that the total value chain delivers the value proposition; or the people could report within a vertical column to someone responsible for a single capability across all the value chains. So, the people doing course design for open courses at Ashridge, could report to the head of open courses or to the head of course design for all types of courses.

Fortunately, there is a rule of thumb to help you decide which way the people should report. The rule says that the default reporting line should be along the value chain (the design people for open courses should report to the head of open courses), unless significant improvements can be made to the value proposition from reporting by capability. In other words, unless reporting by capability significantly lowers cost or significantly improves the value delivered.

The reason for this rule of thumb is that it is easier to create the value proposition and adjust it to match customer preferences, if all of the people doing the work for this value proposition are focused only on satisfying the customer at reasonable cost. The rule of thumb means that the onus is on those who want to organize by capability to create a convincing business case. If in doubt, report along the value chain.

The wonder of the Value Chain Map is that it gives a visual representation of the organisation on one page, showing the core work that needs to be done to deliver the products or services; and it links processes with organization structure.