“The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer.”(Peter Drucker)

This article proposes a conceptual framework for describing business organizations as complex systems, much like live organisms, whose parts function in an orchestrated manner for the sole purpose of creating customer value.

The impetus behind it was the growing realization that while most business publications focus on the tactical aspects of running a business (the “how” of the business), few tackle head-on are the foundational principles of strong business models (the “why” of a business).

Simon Sinek, one of the few voices in the industry to keep reminding businesses to always “start with why[i]”, urges his audience to candidly question the reason why an organization exists and to clearly articulate the way that organization is meaningful to its customers. In reinforcing the idea that businesses can only be successful if they have a distinct reason for being, Mr. Sinek echoes the words of the creators of the Business Model Generation[ii], that a business model must describe the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. Indeed, what the stories of successful organizations such as Netflix, Apple, Samsung, and Girl Scouts of the United States of America (amongst others) reveal is that the best business models are those that are laser-focused on the customer, and where the entirety of the strategic and operational activities are tightly aligned to meet the ultimate purpose of creating customer value. A relentless passion for value, encapsulated into self-enforcing mechanisms for evaluating and pursuing value, is what ultimately makes a business model a winner.

The Mythical Customer Value

Stating that an organization must be responsive to customer value demands is easy. Defining customer value, on the other hand, is a lot harder. The Business Dictionary defines customer value [iii] as “the difference between what a customer gets from a product, and what he or she has to give in order to get it.” This succinct definition demonstrates the challenge. What does it mean to ’get’ something for a product? How can the benefits received or perceived by the customer be defined and measured?

Research done in the 1980s and 1990s by management gurus such as Michael Porter[iv], Christian Grönroos[v]and Annika Ravald[vi]shed light on important aspects of how consumers’ assessment of value is filtered through individualized mental models. These mental models evolve over time, as consumers become increasingly more sophisticated in their expectations for tangible and intangible value attributes. Nowadays, such expectations go far beyond the traditional functional features of a product or service to include aspects such as personalization, fast delivery, local production, minimal environmental impact, child-labor free manufacturing, and support for fair-trade.

Customers’ mental models for perceiving value tend to share common characteristics. Further research into this area has led to the development of ‘perceived value’ frameworks, which provide taxonomies of value attributes used by consumers when evaluating the benefits experienced by purchasing a product or service. Wolfgang Ulaga, in his 2001 article Measuring Customer-Perceived Value in Business Markets[vii], put forth the thesis that value creation in a business-to-business context yields eight types of value: product quality, service support, delivery performance, supplier know-how, time-to-market, personal interaction, price, and process costs.

More recently, a comprehensive study[viii]published by Bain & Company consultants concluded that the way customers assess value closely follows Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – from basic physiological and safety needs to more complex yearnings for altruism, self-esteem and self-actualization. The study, which included a survey of more than 10,000 U.S. consumers, showed that customers’ perception of value coalesces around certain sets of attributes which can be broadly grouped into four categories: functional, emotional, life changing and social impact-driven:

Functional value attributes– include aspects such as “saves time”, “reduces risk”, “makes money”, and “informs” – all aspects reflecting the practical benefits the customer expects to obtain from a product or service.

Emotional value attributes– speak to subjective aspects of value reflective of how the customer expects to feel after consuming the product or service, e.g., it “reduces anxiety”, it “provides access”, or it “rewards me”.

Life changing value attributes– go beyond emotion to appeal to higher-order personal values such as motivation, leaving a legacy, or belonging to a particular group.

Social impact value attributes– speak to customers’ desires to be part of something bigger, something that positively affects the livelihood and well-being of other people.

| Case-in-Point: Microsoft Vista

The case of Microsoft’s Vista operating system, one of the software giant’s biggest flops, serves to underline the criticality of capturing and addressing the customers’ value dimensions. Despite an unprecedented two-year long beta-test program which involved hundreds of thousands of volunteers and companies, Microsoft’s release of the operating system Vista to consumers in 2007 failed to get any of the market segments excited. In fact, the customers’ reactions at the time indicate that Vista failed in all four categories of customer value attributes. The value features consumers expected most from a successor to the popular Windows XP operating system were basic: backward compatibility, increased speed, stronger security features, ease of purchase and installation, and better gaming features. Instead, what customers received was a software product which performed considerably slower than its predecessor when running real-world applications, which was incompatible with the hardware and software on a number of older personal computers, and whose securities features were not much better than in previous versions of Windows. Not only did Microsoft Vista not meet functional value expectations, but it also succeeded in generating negative emotional value through increased user anxiety. |

The Art of Selling Value

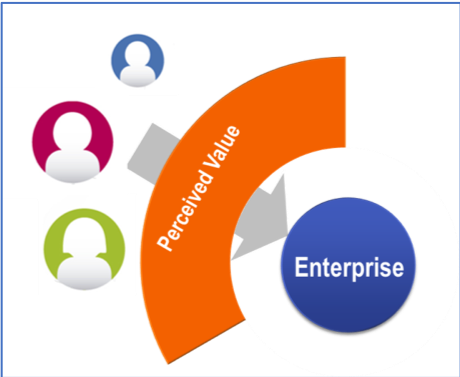

Microsoft Vista’s story emphasizes the crucial importance of performing comprehensive due diligence when analyzing what customers deem to be of value. Companies that understand the criticality of such due diligence have evolved customer-centric operating models which promote ‘outside-in thinking’ in the way they place customers at the core of their decision-making process (see Figure 1).

![]()

Such operating models leverage a variety of analytical methods, from customer journey mapping – a technique that focuses in identifying the customer’s interactions with the business at each part of the journey and the emotional reactions they produce – to customer segmentation, value maps[ix], co-creation workshops[x], human-centered design[xi], social media analysis, and customer relationship management data mining[xii].

Just as importantly, the information distilled from studying the customers perceived valuepreferences must then be translated into a coherent value proposition which demonstrates how the company’s products or services fulfill one or more of the customers’ top value attributes (see Figure 2).

Moreover, the value attributes the company wants to target must be selected strategically, as consumers tend to assign different weights to the various value attributes according to their internal (and often subjective) perception of the derived benefits.

| Case-in-Point: Amazon Prime

Research has shown that online consumers rate the interactions they have with digital businesses according to expectations that the transactions will be quick, painless and intuitive. Not surprisingly, Amazon’s Prime service zeroed in on functional value attributes such as “saves time” (through two-day shipping) and “reduces cost” (through free delivery), which were later expanded to include “provides access” (to streaming media) and “reduces risk” (by providing users with unlimited photo storage on Amazon’s cloud). This strategy proved extremely successful and allowed the company to raise its annual fee for Amazon Prime by over 25% in 2015 with no downsizing effect on its customer base, all the while earning twice as much in sales from Prime customers than from the non-Prime customers. |

Acompany’s value proposition is often the company’s opportunity to make a first great impression with its customers. Successful companies tailor their value proposition to specific market segments and test it through multiple channels to make sure it provides customers with a clear reason to buy the product or service marketed by the company.

Impactful value propositions, advises Quicksprout[xiii]- a company specializing in online marketing – should be razor-sharp clear on how the products or services advertised solve problems or improve situations, what specific benefits customers can expect, and why customers should buy the products and services advertised over the competitors’ similar offerings.

Delivering Value – The Reality Check

As management experts Michael J. Lanning and Edward G. Michaels stated in their 1988 staff paper titled A Value Delivery System[xiv], “delivery of superior value is at the heart of a winning strategy”. As they further noted, superior value is the product of “explicitly and rigorously choosing the superior value proposition” and of ensuring that “each element of the business help[s] provide or communicate the chosen value to the target customer group”. If the value delivered to the market is not in line with the proposed value, which in turn must be a close reflection of the product or service characteristics customers’ perceive as valuable, a company may run itself into the ground building the best mouse-trap ever only to find out the market is not interested in it.

The concept of customer value is therefore a trifecta of perceived value, proposed valueand delivered value, where each one of the three aspects must be a close approximation of the other two. Taken together, the three aspects of value and the alignment between them form the Value Equation (see Figure 3), which stipulates that: Perceived Value »Proposed Value »Delivered Value, where the “»” stands for “approximately equal”.

The Enterprise as a Value Creation System

The Value Equation provides the foundational point of reference for an enterprise, both as a driver and as a constraint for its modus operandi. Bound within the confines of the Value Equation, the enterprise emerges as a conduit for value creation – essentially, as a Value Creation System made up of myriad fixed and moving parts which collude and collide to generate the products or services offered to the market. In fact, the enterprise closely resembles a living, breathing organism, in that it can self-organize, learn, adapt, diversify, specialize, and evolve “emergent properties” such as innovative thinking and conscious risk-taking behaviors. As a result, an enterprise (be it a company, a non-profit organization, an online community, or a City Council) is considered to be a complex adaptive system.

What distinguishes an enterprise from other complex adaptive systems such as the stock market or the cells in an organism is the fact that it is deliberately organized around the creation of value. The enterprise is essentially a Value Creation System designed to ingest ‘raw resources’ such as data, materials, capital and labor power, and produce outputs – services, products, information – useful to and desired by their customers.

Describing a complex system such as an enterprise is not an easy task, given the enormous number of parts, relationships between parts, interactions between the system and its environment, and potential progression trajectories for the system’s components and for the system as a whole. Methods such as agent-based modeling[xv]and complex network-based modeling[xvi], which allow for defining and simulating the behavior of such systems, are useful when studying a particular aspect of the enterprise or the business environment – for example, social network effects, workforce dynamics, or supply chain optimization – but are not yet at the level where they can define the entirety of a specific organization. Moreover, such methods require specialized tools as well as niche research and engineering skillsets, which put them beyond the reach of most executives who are tasked with running the enterprise day-in and day-out and steering it through the treacherous waters of a competitive business environment.

So then, how canexecutives manage and calibrate the intricate system that is the enterprise in any predictable and systematic way? The solution is through approximation – and the best way to approximate is by looking at similar but simpler systems.

The basic building blocks of a mechanical system – for instance, a steam locomotive – are few: a power source (for instance, a steam engine), actuator mechanisms (such as racks and pinions, gears and rails which turn the power obtained from the power source into kinetic energy, or movement, and then relay it throughout the system), and controllers (such as valves or pistons which control the intensity of the transmission of movement through the system). An electrical system, likewise, is composed of only three types of building blocks: the power source (for instance a battery), actuators (devices that turn electricity into other types of energy such as light or heat or movement, and then relay the energy throughout the system), and control devices (such as sensors such as switches and fuses which modulate or turn off the transmission of energy through the system).

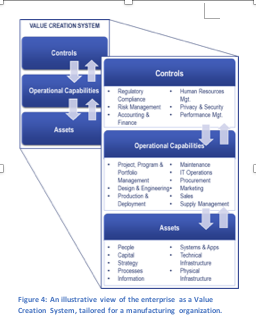

An enterprise is far more complex than a mechanical or an electrical system. Yet, considering all the fixed and all the moving parts in the enterprise, it is apparent that every component within an organization’s boundaries can be classified into one of a handful of types, namely:

Assets– This broad category of elements provides the ‘raw materials’ for the enterprise, such as people, capital, information systems, data, strategy, processes, infrastructure, and more.

Controls– Similar to the way controllers/control devices work in mechanical systems, enterprise controls include functions such as regulatory compliance, risk management, privacy and security management, accounting and finance, and human resources management – all functions which regulate and oversee the use of assets to ensure that it complies with certain rules.

Operational Capabilities– The enterprise’s operational capabilities represent those organizational mechanisms through which assets are turned into outputs in the form of products and services for the target market. While some operational capabilities (such as project management, procurement, and marketing) tend to be universally applicable to any type of organization, others (engineering, car-assembly, crude oil refining – to name a few) depend on the specific nature and mission of the enterprise.

Both the explicit and the implicit connections between the three types of components are particularly significant. While industry-recognized frameworks and methodologies for enterprise-level risk management, regulatory compliance, accounting, project and portfolio management, information systems development and so on have been around for many years, each such methodology has zeroed in only on certain areas of the enterprise. What has been lacking has been a unifying framework binding them together.

Conceptualizing the enterprise as a Value Creation System made up of a finite set of component types which interact through a rich network of internal transactions, all within the constraint of the Value Equation, provides a straightforward way to stitch such methodologies together into a value creation continuum, whose ultimate purpose is the delivery of the value promised to and expected by customers.

The Value Creation System and the Business Ecosystem

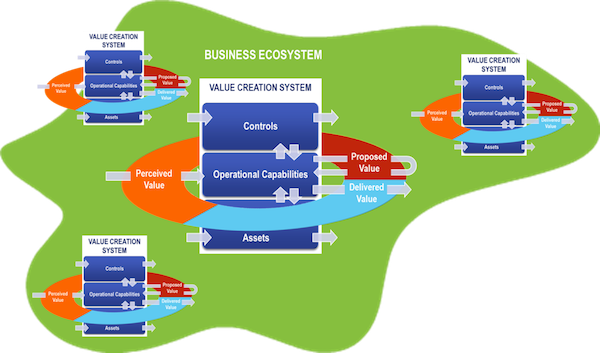

The term businessecosystemwas not a brand-new invention by the time an article[xvii]in Forbes.com, published in 2014, made note of its emergence. The concept of the business ecosystem had been many years in the making prior to jumping into mainstream usage. James F. Moore, in his 1993 article Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition[xviii]had first defined the business ecosystem as “An economic community supported by a foundation of interacting organizations and individuals—the organisms of the business world. The economic community produces goods and services of value to customers, who are themselves members of the ecosystem. “

The word ecosystemis significant because it marks a departure from the static view of the business world as a network of players interacting through more or less impersonal transactions, to an understanding of the economic environment as one where customers, employees, suppliers, banks, competitors interface and exchange value in dynamic, ever-evolving, sometimes collaborative and sometimes adversarial ways. Each one of the participants to the business ecosystem can be thought of as a Value Creation System.

Therefore, within the context of the business ecosystem, the Value Creation System(s) (see Figure 5) act as open systems which continually exchanges controls(regulations, laws, contracts) and assets(capital, people, information, products, services, raw materials) with their external environment. At the same time, each Value Creation System exercises its operational capabilitiesto create and maintain alignment between its proposed value, its delivered value, and its customers’ perceived value – as stipulated by the Value Equation.

![]()

Epilogue

Viewing the enterprise as a Value Creation System which must respect and reinforce the Value Equation provides business executives with a clear and succinct picture of the organization’s value-related priorities, of the points of inflection in the organization, and of its interaction with its external environment. Yet, ultimately, business executives are not alone in steering an organization towards success, and the frameworks presented in this article also point to the types of expertise needed to support the calibration and management of the organization.

Professions such as such as Business Design, Business Architecture, Enterprise Portfolio Management, and Enterprise Architecture are built on practices that cut across organizational divisions to identify and optimize the flows of control and information weaving their way through the organization and between the organization and its business ecosystem.

These disciplines are still considered by many to be esoteric and nebulous, their value hard to measure. Still, until sufficiently powerful algorithms emerge that are capable of strategic planning and management at the enterprise level, the real-world experience in organizational tuning that practitioners of these disciplines bring makes them indispensable to the long-term viability and growth of the enterprise.

Therefore, a continuing increase in the visibility and appeal of such professions is to be expected as more and more organizations adopt system-thinking in their management practices and as the tools used in measuring organizational performance mature.

[i]Sinek, S. (2009), ‘Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action’, Penguin Books.

[ii]Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Smith, and 470 practitioners from 45 countries(2010), ‘Business Model Generation’,self-published.

[iii]Read more: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/customer-value.html

[iv]Porter, M. E. (1980), ‘Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors’, New York: Free Press. (Republished with a new introduction, 1998.)

[v]Grönroos, C. and Ravald, A. (2011), ‘Service as business logic: implications for value creation and marketing’, Journal of Service Management, Vol. 22 Iss: 1, pp.5 – 22

[vi]Ravald, A. and Grönroos, C. (1996) ‘The value concept and relationship marketing’, European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), pp. 19–30. doi: 10.1108/03090569610106626.

[vii]Ulaga, W. Chacour, S. (2001) ‘Measuring Customer-Perceived Value in Business Markets: A Prerequisite for Marketing Strategy Development and Implementation’,IndustrialMarketing Management, Elsevier, Vol.30, n°6, pp.525-540.

[viii]Almquist, E., Senior, J. and Bloch, N. (2016), ‘The Elements of Value’, Harvard Business Review.

[ix]See http://faculty.msb.edu/homak/homahelpsite/webhelp/Content/Value_Map_Overview.htmfor an explanation of the value map technique.

[x]See https://www.visioncritical.com/5-examples-how-brands-are-using-co-creation/for real-life examples of companies using co-creation techniques to drive product development.

[xi]See https://www.usertesting.com/blog/2015/07/09/how-ideo-uses-customer-insights-to-design-innovative-products-users-love/for IDEO’s Human-Centered Design process.

[xii]See resources such http://www.igi-global.com/chapter/customer-relationship-management-and-data-mining/82687on how to extract useful information from Customer Relationship Management (CRM) data and predict customer behaviors.

[xiii]Patel, N. (2014), ‘How to Write a Great Value Proposition’, Quicksprout.com.

[xiv]Lanning, M. and Michaels, E. (1998), ‘A Value Delivery System’, McKinsey & Company.

[xv]See http://www2.econ.iastate.edu/tesfatsi/abmread.htmfor more details on Agent-Based Modeling.

[xvi]See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_networkfor more details on Complex Network-Based Modeling.

[xvii]Hwang, V. (2014), ‘The Next Big Business Buzzword: Ecosystem?’, Forbes.com

[xviii]Moore, J. (1993), ‘Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition’, Harvard Business Review