This is the fourth and final article in a 4-part series of articles on architecture presented by the BAInstitiute. If the reader has not read the previous three articles in this series, the reader is encouraged to begin the series in its proper sequence.

Read: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

In the first article of this series, the reader was asked to visualize how to create a typical low-level workflow model from an enterprise template of architectural primitives or formally defined elements of the enterprise. In the second article, the reader was shown how to build the enterprise template from the DE-construction and normalization (e.g. redundancies eliminated) of low-level workflow models. In the third article, the reader was shown how architecture descriptions are not physical, but primitive. Now it is time to talk about why real architecture is important and how to use the architecture to build something of value for the enterprise.

Why is architecture important?

In the context of an enterprise, the architecture is important because the enterprise changes, evolves and matures over time. Without architecture, one does not have the ability to manage, control and guide the changes over time in an effective and efficient manner. For many enterprises there are no generally accepted, formal or commonly available and shared artifacts or references for use by executives, business experts and IT professionals. Just ask various enterprise personnel and colleagues a simple question: “What is the most useful and important enterprise artifact used in the development and implementation of a strategic enterprise initiative? The answers will vary widely, and rarely will someone refer to a formal architectural artifact. These various answers manifest the nature of the problem, the architecture is missing!

Oh, some may refer to a particular BPM model, various references to essential things or an integrated systems model as an important artifact, but these artifacts represent implementations, something that is already built, fixed, not easily capable of decomposition into its constituent parts since these artifacts were not assembled from its architectural primitives. Please consider this question: Would the reader ever consider upgrading their personal laptop with a faster chip or a higher capacity disk drive or a longer lasting battery or an additional USB port? If the answer is yes, would the reader totally ignore the laptop’s engineering schematics, operating instructions and bill of materials? Of course not! However, many enterprises undertake significantly complicated and extremely difficult strategic initiatives without these kinds of architecture artifacts.

Today, most enterprises have only the implemented systems, composite models and fixed artifacts to research and analyze. For example, if the fixed artifacts are used as a basis for change, then the models must somehow get taken apart, modifications determined from requirements, new/enhancements applied, interfaces changed, then somehow brought back together again as a whole, and prepared for testing and implementation. The “taking apart” and “bringing back together again” are not based on any formal approaches, metaphorically speaking, as one would dissemble and reassemble a laptop, cell phone or tablet using for example, its bill of materials. This informal and undisciplined approach is usually not repeatable and is prone to missing things that require change as well as sometimes incorrectly reconnecting the changed or updated things. This is why architecture is important!

How to use the architecture to build something of value for the enterprise?

If one were to build the enterprise template described throughout this series of articles, then how might this architectural approach drive the implementation of a new strategic initiative?

One must create, metaphorically speaking; the laptop’s engineering schematics, operating instructions and bill of materials. Just remember that all of the low-level workflow models are dynamically created by assembling each from its architectural primitives. And nothing is permanently saved as an implementation model or as a fixed artifact. The architectural approach, metaphorically speaking, uses the bill of material concept referenced in the previous paragraph. But wait a second, those low-level workflow models represent an enormous amount of detailed information, perhaps too much for anyone to comprehend! Therefore, one needs to summarize this valuable information for ease of understanding. So, one needs to aggregate the detailed information up to higher levels of representations, looking at aggregated workflow models or formally integrated components. The aggregation is according to the organizing principle chosen and defined by the Strategic Business Unit (SBU) of the enterprise; and yes, its represents the SBUs bill of materials.

The reader is asked to again consider Mendeleev’s Periodic Table for just a moment. The genius behind Mendeleev’ Periodic Table was that he arranged the elements into rows, in order of increasing mass and in columns so that elements with similar properties were in the same column. Mendeleev’s organizing principle implemented in this new schema became the first universal periodic table. The choice for an organizing principle is incredibly important for an SBU as well. In the 21st Century, a preferred organizing principle is the value stream as defined by James Martin in his book titled, The Great Transition. A value stream is an end-to-end collection of activities that creates a result for a “customer,” who may be the ultimate customer or an internal “end user” of the value stream. The value stream has a clear goal: to satisfy (or, better, to delight) the customer.[1]

The choice of an organizing principle for the Business Architecture reveals much about an enterprise. Why would any enterprise in the 21st Century choose some sort of functionally centric model over a customer centric model based on value streams? The 21st Century Information Age is characterized by the fact that customers can be reached by anyone, anytime and anywhere. Considering for example, the era of social and mobile computing, that obviously means competitors can reach those very same customers, anytime and anywhere as well. In the Information Age, does a functionally centric model represent a mindset characteristic of the previous 20th Century Industrial Age? It does, but in the 21st Century Information Age, the mindset has to focus on the customer (or consumer, client, member, patient, user and etc.).[2]

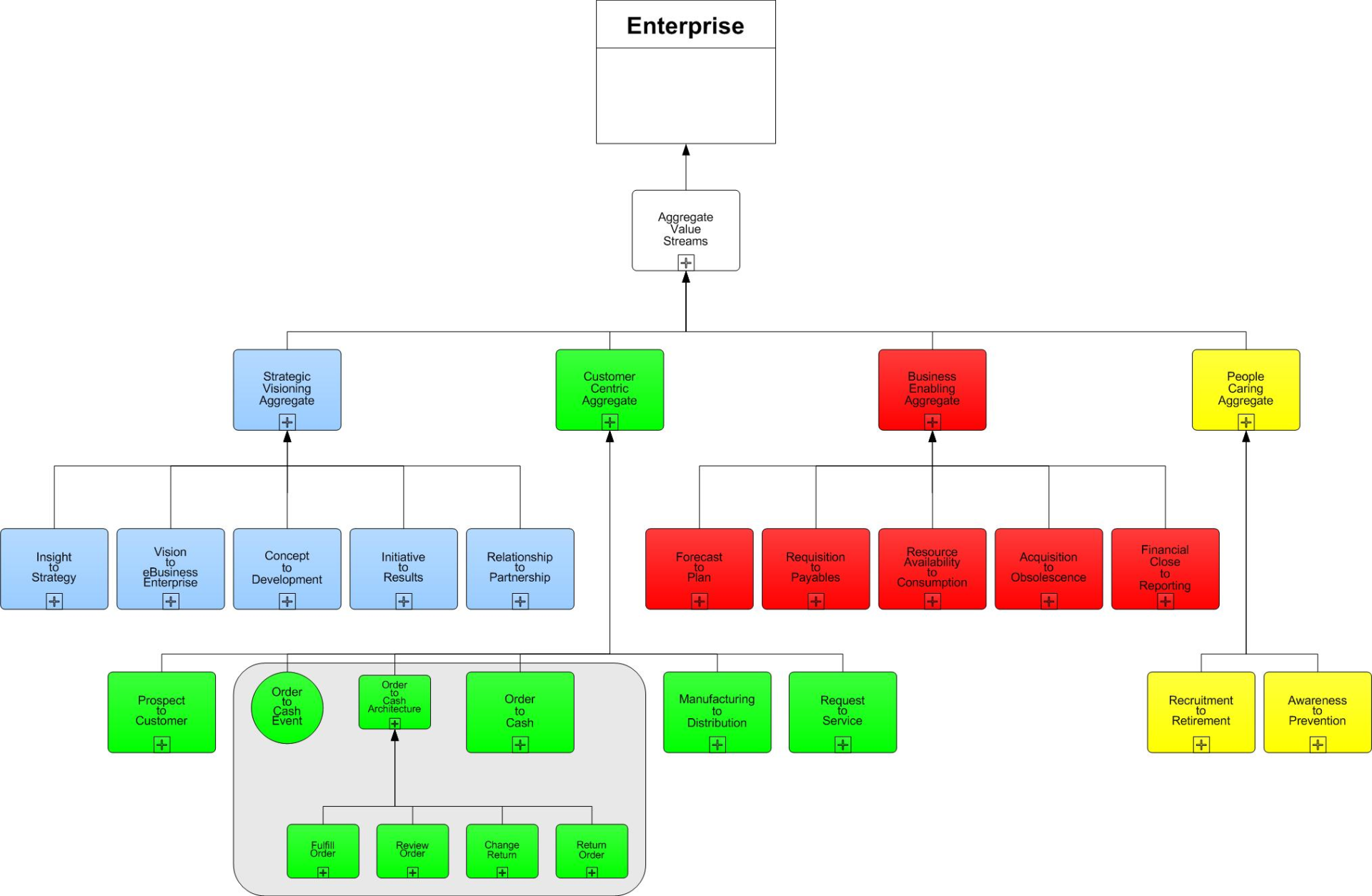

An enterprise Strategic Business Unit (SBU) is a carefully designed and implemented entity. Some enterprises have just the one SBU while others have multiple SBUs. The value streams, just as the SBUs, are carefully designed and also aggregated up from the low-level workflows according to its bill of materials. An example of a SBUs bill of materials based on the organizing principle of value streams is presented in Figure 1. This example represents a fictional build-to-order SBU with 16 value streams aggregated into 4 major groups (please note the group colors blue, green, red and yellow). Given the limitations of this media, the complete bill of materials for this SBU is not presented as the model requires numerous pages. However, a little more detail is provided for the Order to Cash Value Stream in the lightly shaded gray area. The value streams are composite models, aggregations of lower level workflows and therefore, fixed artifacts representing the current implementation of value streams for an SBU in this fictional enterprise. And each is built from architecture primitives which when combined to create a workflow are purposely aggregated up to the value stream level.

Figure 1. Hierarchy of Value Streams for a Fictional Build-to-Order Manufacturer[3]

One can gradually create the architectural primitives workflow by workflow, business process by business process or value stream by value stream until the major and most frequently used ones are complete. This technique is similar to how BPM was incrementally implemented in many enterprises. And after creating the architectural primitives for a few workflows, business processes and value streams, one can say that the architecture is operational and the architects have built something of value for use and reuse across the enterprise.

With these implemented value stream models for a SBU built from architectural primitives, anyone supporting a strategic initiative will have access to real architectural information for research and analysis. Metaphorically speaking, the engineering schematics, operating instructions and bill of materials are available. They may investigate the initiative’s new/enhanced requirements as well as which business processes, procedures, repositories, transactions, organizations, customers, suppliers, partners, financial institutions and so on that are impacted by the requirements. With the bill of materials and other architectural artifacts, they will have the ability to “take apart” and “bring back together again” the SBU using engineering schematics and formal architectural artifacts in a disciplined manner far more effectively and efficiently than even before!

And so begins real Business Architecture in action!

References and Footnotes:

1. Martin, James, The Great Transition: Using the Seven Disciplines of Enterprise Engineering to Align People, Technology, and Strategy (American Management Association 1995), page 104.

2. See http://www.bptrends.com/bpt/wp-content/publicationfiles/09-03-3013-ART-Examining%20Capabilities-Whittle%20%282%29.pdf Whittle, Ralph. “Examining Capabilities as Architecture,” BPTrends, September 2013.

3. See www.enterprisebusinessarchitecture.com , Internet Explorer is required for navigation through the models. Select Case Study tab and follow directions.